åyr We wanted to have this conversation to revisit an interview that you did together in 1998 for the 1st Berlin Biennale catalogue. Back then you talked about your projects in Berlin at a time when the city was undergoing a dramatic transformation. The interview started with your research from the early 1970s, “The Berlin Wall as Architecture.” In some ways the installation that we are doing for the 9th Berlin Biennale at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art is a response to a number of the ideas you discussed. We want to address the ways in which access, separation, and protection are structured beyond the archetypal architectural element of the wall; we are shifting its classical utilization as a divider and nuancing that legacy by looking at the wall as a technology also providing protection and intimacy. These different ideas about walls seem to follow an evolution from your research in early 1970s to some of your most recent projects in Berlin, such as the Axel Springer Campus. Do you remember what you talked about in the interview for the catalogue in 1998?

It’s one of these cases in which a situation with a theory is by definition better than a situation without a theory.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST The catalogue of the first edition of the Berlin Biennale, which Klaus Biesenbach, Nancy Spector, and I curated, was a subverted city guide. We wanted to have Rem’s view on what was and wasn’t happening in Berlin at the time. Back then you were comparing Berlin to a Chinese city, claiming the master plans had failed and that Berlin had produced too much building volume in too short a time for any sort of traditional sedimentation to occur. Eighteen years later, the obvious question is whether Berlin really has become a Chinese city!

REM KOOLHAAS I would say yes and no. Yes, in the case of the extremely rapid production at Potsdamer Platz. The accumulation and assembly of building volumes results from a situation in which architects barely communicate with one another—because they are all driven by commercial interests. This has lead to similar results almost everywhere. But I have to admit, my opinion about Hans Stimmann, who was Berlin’s Secretary of Planning and subsequently Building Commissioner from 1991 to 2006, has completely changed since then. I no longer think that he frustrated creativity, and I actually think that by being so conservative and intolerant he actually saved the city from a lot of garbage. It’s one of these cases in which a situation with a theory is by definition better than a situation without a theory. Or to put it in other words, to a certain extent a strong and dogmatic regime is better than a free-for-all.

åyr Do you think it is possible to draw a parallel between the Berlin Wall and contemporary digital platforms, both being apparatuses or technologies that intensify communication while creating spatial obstacles?

RK The Wall obviously intensified the meaning of the two sides—by creating a reason to communicate.

åyr Your current project, the Axel Springer Campus, is defined by an absence of walls and an immense atrium running across an area on the property once occupied by the Berlin Wall. Openness and communication are achieved through visual connection but not through separation, not through walls.

RK What you are saying just implies that if you had a wall in an office, people would be desperate to know what the people on the other side are doing, but that is not the case. This is not an ideological situation; this is a post-ideological situation. Within an office space, walls wouldn’t have the slightest impact on people’s eagerness to communicate.

åyr When we first proposed our project to the 9th Berlin Biennale curatorial team, we started talking about the Wall as an architectural archetype and as something that is part of Berlin’s DNA. In a way, they actually got a bit scared.

RK I think that the art scene is one of the most conservative at this point in time, and the Wall is one of the few elements that everyone agrees should really not have been where it was.

There’s hardly any loyalty to a place in digital culture.

åyr For us, focusing on the element of the Wall was a paradoxical situation, and I’m wondering if it was the same for you in terms of the Axel Springer Campus, even though your client chose the site. In a way, you did choose to work with that context, because you took the Wall’s original path into account when designing the building. Perhaps this was a pragmatic choice.

RK I’m not saying it’s pragmatic. It really just deals with the consequences of deterritorialization.

HUO When we did our interview in 1998 it was just when the Netherlands had commissioned you to build the Dutch Embassy in Berlin, a major public commission. Now you have more private commissions, such as the Axel Springer Campus with its focus on what you call “digital bohemia.” It would be great to hear more about this new subject.

RK Mathias Döpfner, CEO of Axel Springer SE, explicitly requested us to find a way in which the building could be inviting and make the case for the digital elite of what he calls “bohemia.” This is interesting, because there’s hardly any loyalty to a place in digital culture. Place is always shifting. He thought he needed a building that articulated this shift, and that its deliberateness would act as a tool for mobilizing the brightest people from that context.

åyr We see the Springer project as embodying the transformation of Berlin into a kind of European Silicon Valley, a place where there is a strong start-up culture. Is this project trying to address that condition in terms of office design?

RK What I really appreciate about Mathias Döpfner is that although he is totally European, he has steered the company towards the digital, almost without hesitation, which is extremely rare. They are clearly fascinated by Silicon Valley, almost to the point of caricature. Yet they didn’t import Silicon Valley culture wholesale. I think they are really at the forefront of wanting to define a European opposition to the imperialistic dimension of Silicon Valley. Start-up culture is by definition a culture that can invade any environment and feels most at home in buildings that are not new. Our building has a European approach. Informality and domestic pampering are not present in this building at all. In a sense, it’s a Prussian building of the digital era.

åyr The Springer project is one of the very few contemporary projects that tries to deal with the digital, not in purely aesthetic or technological terms but as a “form of life.” There is a strong emphasis on this building as conceived for people who are constantly connected. We’d be interested to hear how this has affected your design. Orientation, communication, experience— all these things are transformed by devices, whereby architecture often seems to stay the same.

RK That issue is totally unconnected to Springer. Maybe it is relevant to a series of projects that started with the Universal Studios headquarters in Los Angeles. We are addressing two questions here: How does a very complex organization function as a whole without suffering from total fragmentation? And how can one address the danger of fragmentation present in any digital office? Today fragmentation is not dependent on physical isolation. For example, in OMA’s recent project for the G-Star Raw Headquarters we created a quite complicated split-level situation. In the end, they told us that the entire company sent 60 percent less emails. For me this is the greatest compliment, but it also points to the greatest potential achievement for architecture now—reintroducing physicality into this endless flow of information, which is not only so incredibly redundant, incredibly irritating, incredibly exhausting but also gives everyone a false sense of real productivity.

åyr So how do you think the administrative or organizational role of architecture has moved onto digital platforms? Is architecture now able to be a bit freer, more liberated? Now that digital platforms have become more mature, one can observe a return of materiality—or, more precisely, the possibility of a return of the wall, but a wall which is friendlier, stripped for some of its modernist violence. In the 1990s architecture was dominated by parametric dreams and the rhetoric of openness, unpredictability, and newness. All of a sudden we don’t want this so much anymore. There is a greater interest in small rooms, a booth, a nook— more legibility, more intimacy, another materiality. This is the genealogy we are showing—from “The Berlin Wall as Architecture” to the pierced cozy wall of contemporary office design.

Our building has a European approach.

RK It’s not simply that architecture is becoming digital or that we can use the digital to make interesting architecture. The digital world is a world of totally different adventures, of conceptual, mental spaces. So maybe architecture can focus on exactly what you’re describing—physical and material experiences and the various emotions generated or offered by those experiences and not available in cyberspace.

åyr We are skeptical of chaos as a means of creating the unexpected—and causing people to shop more, talk more, and communicate more. We would speculate that maybe now we have enough solicitation coming from our devices, and therefore what is somehow desired are quiet spaces. I was just reading this morning on Facebook that most video adverts on Facebook are played without sound. This is a new approach that could be applied to architecture. Not to the degree of Peter Zumthor though … [Laughs]

We guess this comes from a certain frustration of our generation, which has grown up in the architectural discourse of the mid-nineties and the early two-thousands, when the canonical architectural values of institutions and collective spaces were guided by the intention to smooth boundaries, open up, and enhance communication and visibility.

RK Well, larger obstacles keep arising, of which security is one. This presents some very serious contradictions: the aesthetic of continuity and the security-thinking of enclosure and protection.

HUO I have one last question: In our conversation in 1998 you said that Berlin was very scary in the way its modernism was performing an exorcism on the city. So, is Berlin still scary eighteen years later?

RK I’m surprisingly indifferent to it. I’m not outraged by it.

åyr What about your own relation to technology. Do you have daily experiences with Uber, Airbnb, these kinds of things. In terms of your identity, is this part of your experience?

RK Not really, because I have no real need for it. Well of course in terms of getting tickets, in terms of making reservations, of course. OK, next question.

åyr On a more general level, what is your relationship to contemporary art? Are you interested in it?

RK Your question is really crazy. Why are you asking this? This is just gossip: But anyway, I think your projects are really interesting, but as I said earlier, I feel more like a participant than a subject.

This conversation is the edited and condensed version of two conversations between Rem Koolhaas, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and the members of åyr on February 12, 2016, at the OMA offices in Rotterdam and on February 21, 2016, at the Ambassade Hotel in Amsterdam. åyr (formerly AIRBNB-Pavilion) is an art collective based in London whose work focuses on contemporary forms of domesticity.

åyr was founded in 2014 by Fabrizio Ballabio, Alessandro Bava, Luis Ortega Govela, and Octave Perrault. The collective was formed in occasion of an exhibition inaugurated during the opening days of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, which took place in apartments rented on a flat sharing website. Through performances, installations, and writing, åyr investigates the relationship between objects and their environments and the effects of the internet on the city. åyr is not connected to or endorsed by Airbnb, Inc. or any other Airbnb group, company, or affiliate.

REM KOOLHAAS founded OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) in 1975 together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis, and Madelon Vriesendorp. He graduated from the Architectural Association in London and in 1978 published Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. In 1995 his book S,M,L,XL summarized the work of OMA in “a novel about architecture.” He heads the work of both OMA and AMO, the research branch of OMA, operating in areas beyond the realm of architecture such as media, politics, renewable energy, and fashion. Koolhaas is a professor at Harvard University where he conducts the Project on the City. In 2014, he was the director of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, entitled Fundamentals.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST (born 1968) is a curator, critic, and art historian. He is Codirector of Exhibitions and Programs and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London. Obrist is the author of The Interview Project, an extensive ongoing series of interviews. He is also coeditor of the Cahiers d’art revue.

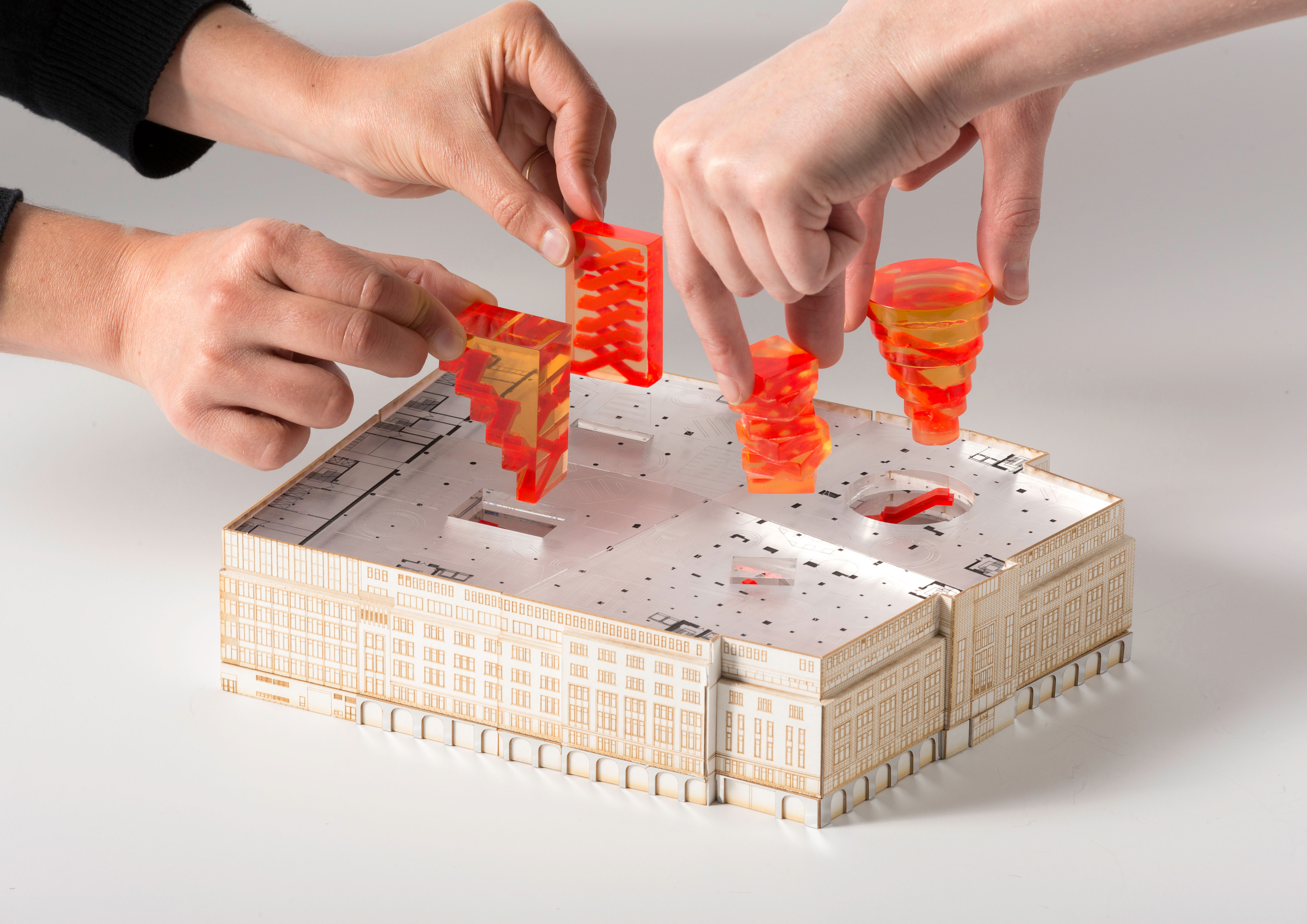

IMAGES: åyr, Berlin Feature Wall, 2016; åyr, home is wherever I am with you, 2014, AIRBNB-Pavilion, Instagram; åyr, #my space of reproduction, 2014, AIRBNBPavilion, Instagram; OMA, concept model of the Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe) renovation; OMA, interior view of the Axel Springer Campus; Rem Koolhaas/OMA, Berlin field trip, 1972