A micro-trend, as I understand it, doesn’t last the time it generally takes to be recognized as a proper trend. It burns out because it flares too brightly, too quickly. But micro-trends are often what later inspire larger trends. Something that was too blatant or obvious to become fashionable at its inception but is later recontextualized as a relic can ultimately become a signifier of its era. And this has always been the case. The least chic trends of a decade are always revived twenty years later, almost without fail. But lately, the very format of contemporary reportage has microtized many trends with proper potential. Dynamiting infant trends makes them micro, and this is now easier than ever.

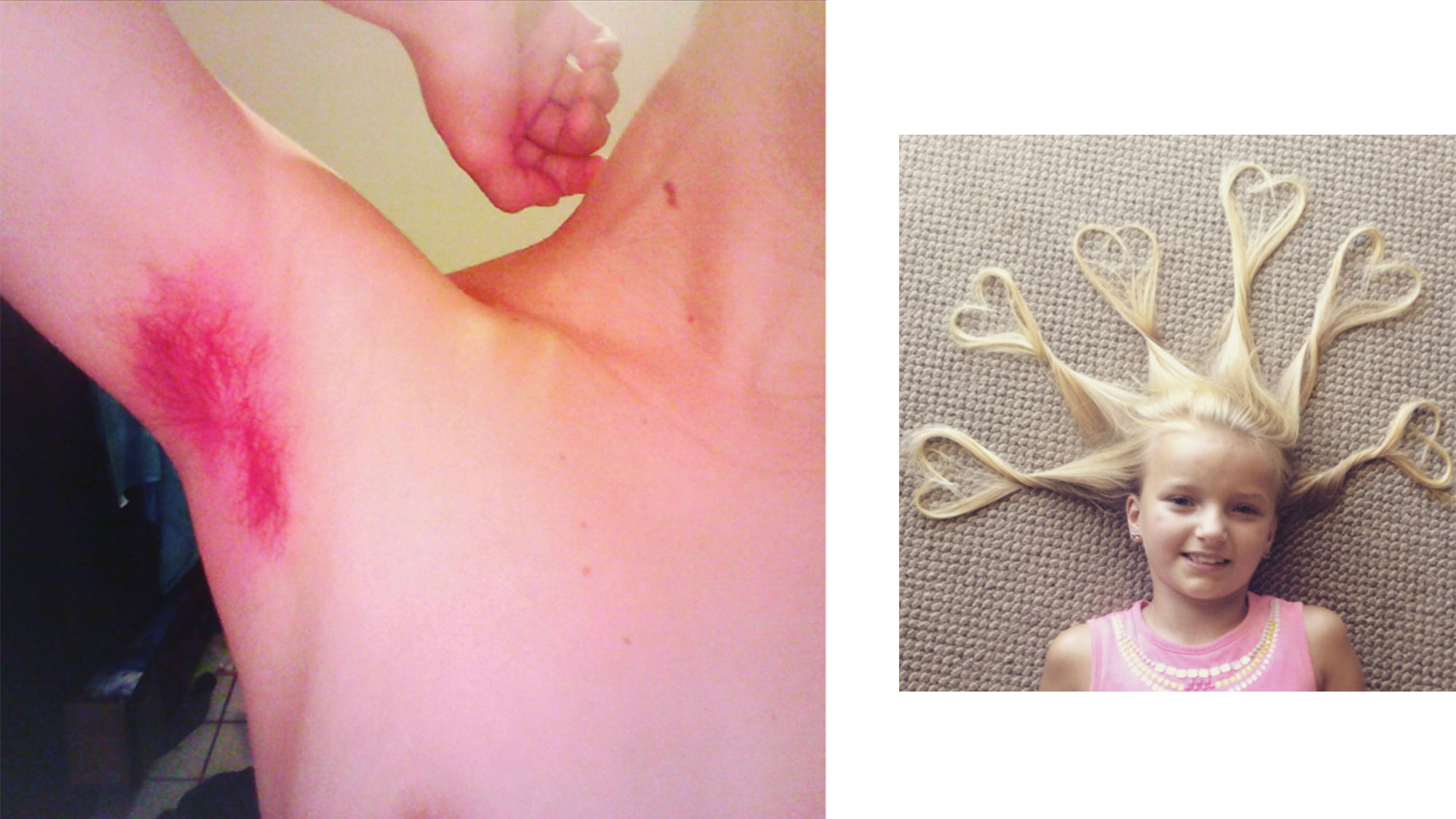

Being short-lived is not the only factor that makes a trend micro. The trend may be followed too wholeheartedly within one age group, for example. It could be a cheap accessory that started too low on the supply chain to trickle back up to high fashion during its first time around. A phenomenon could be bubbling underneath a broader fashion narrative for some time, before it is discovered as something even slightly tangible. Take a T Magazine article from July 2015 about dying armpit hair. The story goes: Manic Panic colors are in style for young women who don’t shave their pits this summer. Actually, as anyone knows, this is an uncommon practice with obvious setbacks, and one that can really only be sustained—as something, quite literally, cool—in images. “The internet, it turns out, is up to its armpits with women who dye theirs,” writes Andrew Adam Newman. “Miley Cyrus displayed her newly pink underarms in a photo she posted to Instagram, drawing more than 396,000 likes and more than 30,000 comments. On Instagram, more than 700 photos of women (and a handful of men) have been posted with the hashtag #dyedpits. And a blog post by Roxie Hunt, a Seattle hairstylist, ‘How to Dye Your Armpit Hair’ has been shared more than 37,000 times since it was published in October.”

Trusting these numbers when it comes to fads blatantly ignores the information that journalists tend to keep in mind when it comes to anything else. An article in Popsugar claims that keeping track of emerging hashtags is important, because “#normcore was the most Googled trend of 2014,” insinuating that because something is Googled a lot, it makes a big impact on the economy or actual fashion. Just because something Miley Cyrus posted got a lot of attention or appreciation does not make the content of the post a trend. And just because something as unusual as a woman putting semi-permanent color on a body part notorious for sweatiness was a topic shared by many does not equate to a group of people automatically following these instructions. It makes the topic a trending one.

The first sign that people don’t really understand how these things work is that they treat the internet as if it were a place.

Take the #heelconcept, a meme (to be differentiated from a micro-trend by its very deliberate countercultural intention) that started a year ago and continues today. Rolling its eyes at prevalent phenomena ranging from photographing high heels to the emergent obsession with bedroom life on social media and a forced aesthetic connection to feminism, the heel concept bluntly negates the concept of fashion trends. Examples of the meme place a foot in a still life that loosely represents the shape of a high heel, which could never become an actual high heel. No strap holds the structure to the foot, or the heel is made of liquid, or the shoe is rooted to the ground. No designer could steal these concepts without bastardizing what made them so evocative—that they are part of the outside world, staged on taupe wall-to-wall carpet, using drugstore products, and are impossible to place on a walking model. They are not a part of the insular fashion world, nor do they want to be. They are untrendable fashion.

If a trend can come and go before a magazine has time to print it, perhaps it was really an event. Since social media started, runway shows that are put on a whole season ahead of time sometimes end up accidentally dictating the current season. That’s because the world can see everything in fashion as it is happening, not months after, in the ads. Of course, it’s all one and the same. A micro-trend—like dyed armpit hair or impossible shoes—is still part of the fashion cycle, and always has been. The styles seen on runways borrow from concepts found in micro-trends or untrendable fashion, which come from Instagram, and before Instagram existed they came from clubs, raves, protests, secret societies, etc. The runway has always been late in this way—and magazines even later—although both are often sourced as a trend’s earliest sighting. That’s fashion’s job: answering to, solidifying, or codifying something that’s already in the air. That concept is then translated into wearables, or it’s co-opted by a pop star, a store display, or a T article. The message—the concept now formed by a large group of contributors over time—has made its way to more than just the ether. In its nuanced anarchism, the heel concept, for example, is woven into the fabric of a larger trend; it assumes a mood that is a reaction to—not an iteration of—so-called street style.

Personal style can never, in fact, become more personal. It can only become more widely

known as one’s own.

An article I recently skimmed listed a few “Instagram stars” who have worn bonnets in selfies. “Is #bonnetcore the Next Big Street Style Accessory Trend?” it asks. Most of the images in the ad-riddled slideshow are taken from Instagram, and they show sarcastically pouting people—like stylist and designer Jake Levy and actors Lauren Avery and Lily Rose Depp—in staged pastel portraits and not caught on the street outside a fashion show. Another article I half looked at the other day mentioned that babies might be trending, because they were showing up a lot on runways. Another one, “Mourncore: Hot New Trend or Something We Invented on a Summer Friday?” And “Individuality is Trending.” A response piece to #bonnetcore called out those reporting on and tagging “trendlets” (including plastic bag onesies and heart-shaped hair selfies), saying that because of the way they’re blasted out, they’re always exhausting, and that naming them a trend immediately kills them. Strangely, this article made sure to point out that normcore, in contrast, is “very real.”

A prevalent trend I’ve noticed lately in fashion is that journalistic integrity is something now deemed outmoded by brands and corporate-run magazines, and that the readers are pissed off. Trending now is outrage at trend forecasting. Backlash is never far from any trending topic, although this particular type of backlash, or meta-trend, is fraught with self-loathing. Those who point out that new ways of reporting are too enmeshed in attention-seeking to be trustworthy, they are invariably seeking attention themselves. One upset op-ed demonizes the rest, and it all starts because someone at an aggregation site had to post a certain amount a day and gain a certain amount of traction over time. No wonder that the natural impulse for writers forced to create content every few minutes is to focus on something as serene and simple as bonnets and babies. Those things, they must know, are not trends. But they are welcome reminders of bliss—the straightforward focus it takes to milk cows in the countryside or breastfeed.

It’s not that fashion has actually become faster. “Fast fashion” is certainly a problem, because it puts a greater stress on the system of irresponsible labor practices in the fashion industry, and it might seem logical to blame this on the internet’s quick proliferation of fashion trends. But trendiness has not, in my experience, become a bigger priority over the past few years. The idea that people (meaning a relatively large percentage of the population) go into a frenzy over some new street style phenomenon is inaccurately reported. Over the past decade the only difference that the internet has made in terms of how we view fashion trends is to help reporting become much easier to monetize, and so sensationalist journalism has become more accepted. This is due to a shift in the way we view our media. We filter it through our friends. If our friends can get us to look at something easily, advertisers want to make sure our friends are sharing their stories, whether via a site with which the advertisers are affiliated or through a direct link to a product. Trends, just like all trending items on our feeds, must somehow seem to be at a critical mass to become newsy enough to be shared. Bonnets are not trending, but still lifes are, because Instagram is. But it won’t be forever. That space too is a metatrend. It’s something that overwhelms the industry of trend forecasting, fashion, and art and yet is a trend itself. Trends are trending. Isn’t it boring?

Another article I read a little while ago purported to be an essay about shifts in personal style. It argued, I think, that because it is easier to acquire clothing almost immediately after discovering it, and because clothing production now allows for a wider array of specific trends made for mass consumption at low costs, personal style is becoming more personal. This view seems narrow, seeing as it relies almost completely on cheap labor. Again, an author (most likely working under a tight deadline) has missed the mark, in favor of a quick and shoppable analysis. Personal style can never, in fact, become more personal. It can only become more widely known as one’s own.

When it comes to measuring fashion, before and after the advent of the internet, it’s the coverage that’s changed the most. Fashion coverage is of a different texture than the once-a-month trend forecasting from the heyday of magazines. Personal style blogs have become more financially successful than most magazine websites. Compared to the web component of an existing print magazine, blogs have smaller overhead and are so far viewed as more trustworthy in terms of styling and advice—meaning that readers have become wise to magazines’ relationships with advertisers, while a blogger’s product placement negotiations are harder to spot. And luxury brands notice bloggers and their influence, they notice the importance of street style and social media, and they are paying more attention to e-commerce than ever before. Therefore, magazines seem to be less and less a part of the equation. But it is the job of the magazine not only to understand these developments but to represent and report on them in artistic ways. As a periodical, a magazine becomes a capsule of cultural climate. Some periodicals see this—having always known this. Those become the best stethoscopes for fad pulse-points and, later, the best references of a time period. They will attempt to recognize a micro-tend before reporting on it, and jump to no conclusions. Some trends are best left ignored until they are blazing in full glory. The rest, which, even after decades of cultural relevance, cave to the newly established pressures of guaranteeing their advertisers a flash flood of views, will unfortunately burn out.

NATASHA STAGG´S first novel, Surveys, was published in 2016 by Semiotext(e). She regularly contributes to DIS magazine, Kaleidoscope, and other art journals, and she is the Senior Editor of the New York fashion magazines V and VMAN.

IMAGES, top to bottom, left to right: Lauren Avery, #bonnetcore Instagram, 2015; Daniela Fernandez, #dyedpits Instagram, 2016; _jo_loves_, #hairhearts Instagram, 2016; M.sty, #heelconcept Instagram, 2015; Jake Levy, #bonnetcore Instagram, 2015