Artist Simon Fujiwara enlisted his economist brother Daniel to consult on The Happy Museum (2016), his project for the 9th Berlin Biennale. Daniel is an expert in the growing economic field of Happy Economics—a trend in which happiness and well-being are valued and monetized. What is the value in Euros of the happiness gained from dancing, per person, per year? Daniel Fujiwara’s company Simetrica could give you an exact figure, helping you to decide if it is worth it to you. This conversation took place leading up to the exhibition.

SIMON FUJIWARA Can you describe what Simetrica is, the company you have founded?

DANIEL FUJIWARA Simetrica is a research organization that uses economics and other disciplines such as philosophy, behavioral science, and neuroscience to understand human behavior, feelings, and values, in order to better comprehend the impact of policies and actions on society’s well-being. Our work is technical and quantitative in that we use a wide range of mathematical and statistical concepts and tools, but all of our work is also grounded in a highly structured and detailed ethical approach, which draws on key areas of normative ethics and applied ethics. To give you a more concrete example, we have been working on what value means in the arts and culture and how we can measure it. We have been doing this work for a number of governments and arts councils across the world.

SF So to put it simply, the goal is to help organizations understand how they impact the well-being of people in society. There has recently been a big wave of companies that believe their image is not just about the products they sell but their effect on the world. This idea of doing good or making people happy has become an advertising ploy. Do you see the work you’re doing as related to this, or do you think something else is happening? Do you think there is genuine good being done?

DF This is a really tricky and interesting question, because it depends to a large extent on how we define doing “genuine good.” One ethical approach to thinking about “good” is to evaluate an action only in terms of the outcomes that it produces. This is known as consequentialist ethics, and within this way of thinking we would conclude that companies doing good are genuinely doing good. But in many cases, outcomes are not the only way to evaluate an action. Deontological ethics holds that issues such as the process behind an action, rights, and duties are also morally important. In this sense we may also care about the intentions behind an action. If we feel that it is wrong to do “good” community work only with the intention of making more profit, then we would have to say that those companies giving back to society out of self-interest are not doing “genuine good.” We actually find that the motives and intentions of companies really vary; some companies do think about the bottom line and their profits as part of their corporate responsibility. They may believe that if they have good social responsibility schemes and if their employees volunteer, that will look favorably on their company image and hence boost profits. But, as I said, whether this is right or wrong is an ethical question. Our particular standpoint is that all organizations, public or private, have a social duty to improve the wellbeing of people, animals, and the environment over the long term.

We could measure the value of a car or a social experience by looking at how much people shout about or discuss them on social media.

SF How do you feel about the relationship between technology and human life, the direction it’s going?

DF In our field, technology has been a huge benefit in terms of collecting data from lots of people in real time. It really allows us to get a better understanding of what is important to our lives and what makes us happy. Historically we’ve never had that kind of data before. It allows us to test our philosophical assumptions: What is happiness and what makes us happy? As long as we all use this data in a safe and responsible way, and people consent to it being used for the purposes of research, I think it can make our lives better, and it is already doing so in many countries across the world.

SF It’s funny—in many of our conversations over the years, one thing that has become increasingly clear is that due to your work as an economist—in a field that’s pushing things forward in quite a radical way—you are willing to accept new modes of thinking that radically break with the old. In a sense, this makes you adopt the traditional avant-garde position that artists used to occupy. In contrast, I as an artist and many individuals of my generation with whom I discuss your work, almost come across as reactionary and conservative, because we say: “Hey, wait, we don’t want economists or scientists to colonize and quantify every aspect of human life. We do not need to know about human happiness to experience it. We need to retain an aspect of mystery, to believe that life is more than knowledge.” It’s almost as if by having access to so much information through the internet, we long for a kind of self-imposed ignorance, like the peasants in Galileo Galilei’s time who refuted his astronomical discoveries to preserve the magic of the skies. Where do you see such attitudes within the spectrum of your work?

DF Economics is a very exciting field, as we love to learn and borrow heavily from lots of other fields, such as philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, math, physics, and biology. This interdisciplinary approach is my main area of research, and it is what we do at Simetrica. Certain areas of our work and research definitely have a heightened sense of romanticism in many ways, areas which many of us think should not be the subject of quantitative or technical research and analysis. I feel, however, that quantification and measurement is one key way of helping us to better understand the phenomena that surround us, and in this respect, people’s well-being and happiness is no different. As a discipline, we have certainly learned a lot about what happiness is and what makes us happy, and we are now just starting to be able to respond to some of the key questions about happiness that were posed to us by the likes of Aristotle, Epicurus, Jeremy Bentham, and John Stuart Mill, which I think is exciting. But we must understand that any discussion about happiness and the measurement of happiness has to be grounded in a proper philosophical or ethical debate and approach. This is absolutely key for me, and it shows in our work. Art has an important place in society in terms of how it relates to human well-being. Our research consistently shows that people who are engaged with the arts and cultural activities have higher levels of well-being, as measured on lots of different scales, such as life satisfaction, happiness, feeling relaxed, and having a sense of purpose in life. Artists along with teachers have the highest levels of purpose in their lives. There are lots of other interesting findings here too. For example, we find that being interested in the arts (going to see films, visiting galleries, going to the opera, etc.) is great for one’s happiness, but it is even better if you go to these events and activities alone. The wellbeing data is just starting to allow us to paint a picture of how the arts impact our happiness. Because the arts have positive implications for our well-being, they hold benefits for society. Our future research will focus on this in more detail.

SF Since you mention visiting galleries alone, do you have any reflections on the increasing individualization of society, and do you feel that your work is promoting it? The fact that we’re becoming increasingly detached from family and community approval and more dependent on selfjudgment— do you accept that as a good thing?

DF The process of individualization was set in motion by the thinkers of the Enlightenment period, and so I think we have been on this trajectory for a long time. In fact, the current research on wellbeing in many ways has its roots in Enlightenment thinking. What is interesting is that by asking people about how they feel as individuals, we have found that many societies are still very non-individualistic, and that individual happiness is hugely dependent on community engagement and involvement, and relationships with others. By understanding more about individuals and their happiness, we have affirmed that society and interconnectedness are key to human life.

What exactly does a dementia patient get from touching Neolithic bronze sculptures?

SF What would you propose as a nonmonetary word for valuation? Instead of saying something creates “x pounds,” what would it create? How does looking at a van Gogh impact us? Or what exactly does a dementia patient get from touching Neolithic bronze sculptures? What and how are these outcomes described?

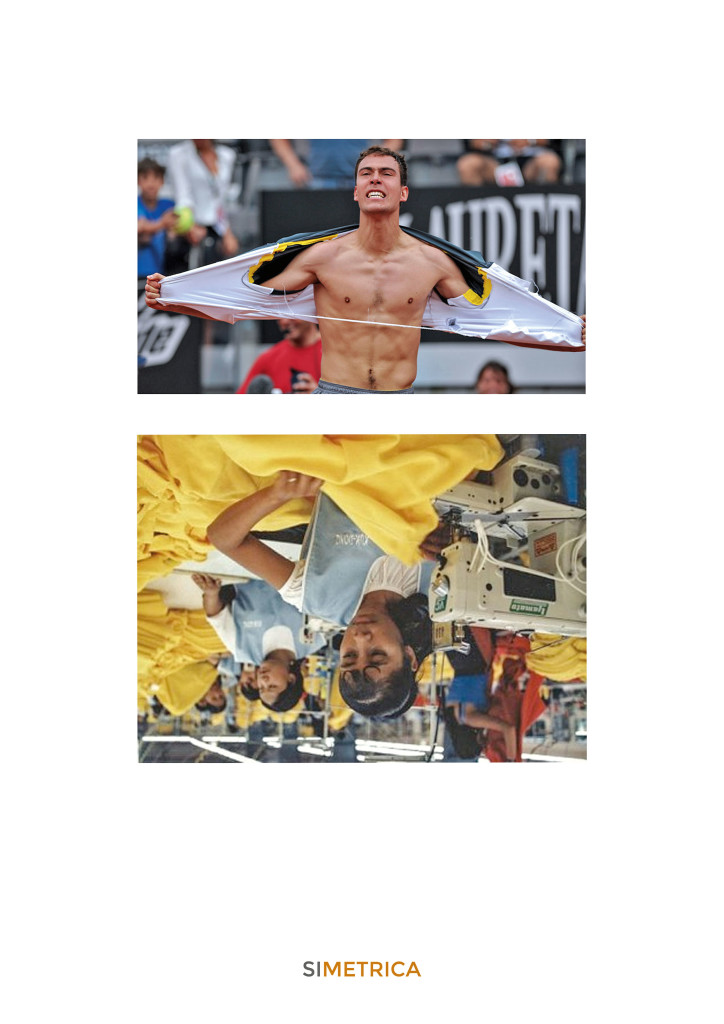

DF To be precise here, the term “valuation” has no a priori link to money. Value, in its purest sense, is simply a gauge of how strongly we feel about or care for something. Value is an inclusive concept, which applies to any sentient being and not just humans. That is, elephants, whales, and dogs can perceive value just as we do. Value can be described and measured in many different ways, for example, how wildly a football player celebrates when he scores a goal, how quickly a dog gobbles up his meal, how loudly a child cries when her favorite toy is broken, how much we are willing to pay for something, how much time we are willing to spend on something, how much effort we put into defending something, and so on. We could use these behaviors and actions to measure the value that people place on certain market or non-market goods, services, and outcomes. Monetary valuation is just one form of valuing something. I think it gets a bad name in some quarters, because the meaning is used loosely, and often it is not employed in the same way that it is used in economics. In economics the monetary value of something like a car or social experience is the amount of money it would take to improve someone’s quality of life and well-being to the same extent that the car or social experience does. Money is literally just a quantitative gauge of how much people’s quality of life has improved, just like degrees Celsius is merely a quantitative gauge of heat or cold. For example, we could measure the value of a car or a social experience by looking at how much people shout about or discuss them on social media, but policy makers like monetary valuation, because you can compare the benefits of a policy to its costs in the same terms. For people who like van Gogh, looking at a van Gogh will create a valuable experience, which we could measure in monetary terms (and we have done so in the past for various museums), but which we could equally measure in non-monetary terms by assessing how long they spend looking at the painting, how much they say they enjoy looking at the painting, and so on. A similar process would apply to the valuation of any other item, experience, or outcome. An example I like to consider is a football player who scores a goal against the same team in one season and again in another season, but the value of each goal differs considerably due to the different circumstances that prevail at each time. The first goal leads to the team winning something, whereas the second goal is almost meaningless for that match and the team’s season. The way that the player celebrates will be very different for those two goals, although the settings and parameters are identical (i.e., a goal against team x). So we can look at value in terms of behavior—in terms of how wildly the player celebrates after scoring the goal. Does he give a few high fives, or does he rip his shirt off and jump into the crowd? That’s the first order of magnitude for thinking about value—looking at it through behavior. Then we may need to think about quantification. In economics we would do this by looking at how someone’s quality of life is impacted on scale of zero to ten, for example. The first goal would improve the player’s quality of life and well-being much more than the second. Then we could go one step further, taking that scale and monetizing it into something. So what does an improvement from two to four on that quality-of-life scale mean in monetary terms? What does it mean in other quantitative terms? The question is how far we can quantify that person ripping of their shirt and screaming and yelling—that feeling!

SIMON FUJIWARA’s The Happy Museum (2016) is a collection of artworks, everyday objects, advertising, clothing, performances, and videos that explore Germany’s material expressions of happiness in the 21st century.

IMAGES: Simon Fujiwara, Hello, 2015. Courtesy of the artist. Simon Fujiwara, advertisements for Simetrica, 2016.