Time is changing. Human agency and experience lose their primacy in the complexity and scale of social organization today. The leading actors are instead complex systems, infrastructures and networks in which the future replaces the present as the structuring condition of time. As the political Left and Right struggle to deal with this new situation, we are increasingly wholly pre-empted and post-everything.

Time Arrives From the Future

Armen Avanessian: The basic thesis of post-contemporary is that time is changing. We are not just living in a new time or accelerated time, but time itself — the direction of time — has changed. We no longer have a linear time, in the sense of the past being followed by the present and then the future. It’s rather the other way around: the future happens before the present, time arrives from the future. If people have the impression that time is out of joint, or that time doesn’t make sense anymore, or it isn’t as it used to be, then the reason is, I think, that they have — or we all have — problems getting used to living in such a speculative time or within a speculative temporality.

Suhail Malik: Yes, and the main reason for the speculative reorganization of time is the complexity and scale of social organization today. If the leading conditions of complex societies are systems, infrastructures and networks rather than individual human agents, human experience loses its primacy as do the semantics and politics based on it. Correspondingly, if the present has been the primary category of human experience thanks to biological sentience, this basis for the understanding of time now loses its priority in favor of what we could call a time-complex.1

One theoretical ramification of the deprioritization of the present we can mention straightaway, but will need to return to later, is that it is no longer necessary to explain the movement of the past and the future on the basis of the present. We are instead in a situation where human experience is only a part of — or even subordinated to — more complex formations constructed historically and with a view to what can be obtained in the future. The past and the future are equally important in the organization of the system and this overshadows the present as the leading configuration of time.

Complex societies — which means more-than-human societies at scales of sociotechnical organization that surpass phenomenological determination — are those in which the past, the present, and the future enter into an economy where maybe none of these modes is primary, or where the future replaces the present as the lead structuring aspect of time. This is not absolutely new, of course: for a long time political economy and social processes have been practically dealing with the subordination of the human to the social and technical organization of complex societies. Equally, under the heading of Speculative Realism, philosophy too has recently been trying to reset the notion of speculation as the task of finding more-than-human forms of knowledge by establishing the conditions within conceptual thought of knowledge of what is beyond human experience. That project is certainly attached to the conditions of the time-complex but is also distinct to it —

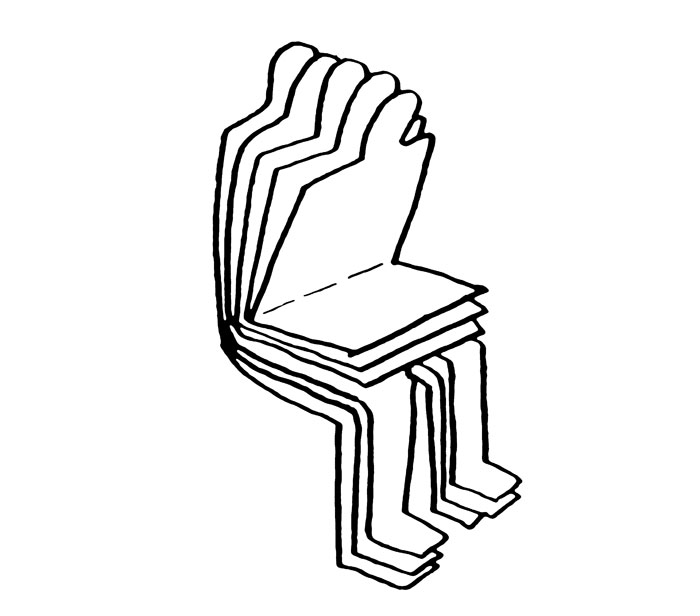

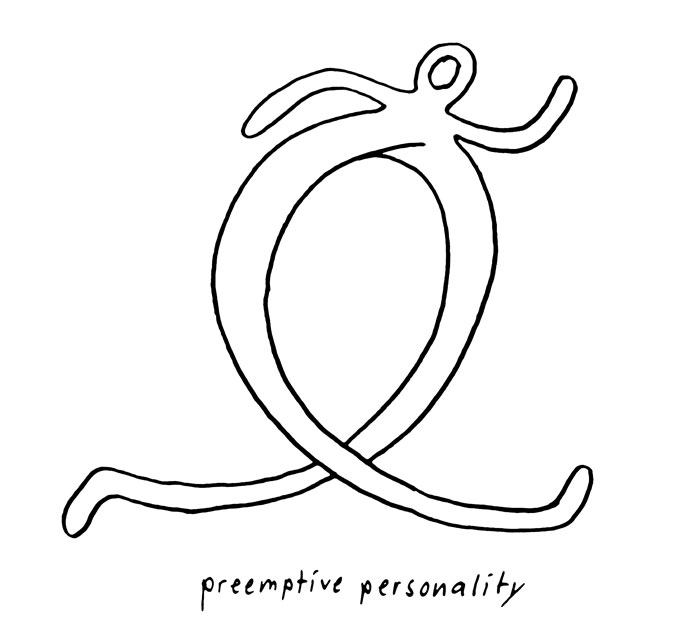

AA: – And to some concrete examples of the speculative time-complex that we know from everyday experience or from daily news. These are phenomena that usually start with the prefix “pre-,” like preemptive strikes, preemptive policing, the preemptive personality—

SM: Could you outline these phenomena?

AA: What has been called preemptive personality or personalization is how you get a certain package or information about what you might want that you haven’t explicitly asked for from a commercial service.2 We know a version of this from Amazon: its algorithmic procedures give us recommendations for books associated with one’s actual choices but the preemptive personality is one step ahead: you get a product that you actually want. The company’s algorithms know your desires, they know your needs even before you become aware of them yourself. It doesn’t make sense to say in advance that “I’ll send it back” because it is likely that it will be something you will need. I don’t think that all this is necessarily bad, but we do have to learn how to deal with it in a productive or more pro-active manner.

We no longer have a linear time, in the sense of the past being followed by the present and then the future. It’s rather the other way around: the future happens before the present, time arrives from the future.

Another thing, often criticized, is the politics of preemptive strikes, which is also a new phenomenon of the 21st century. Brian Massumi and others have written about the kind of recursive truth they produce: you bomb somewhere and then afterwards you will find the enemy you expected.3 You produce a situation that was initially a speculation. The logic here is recursive and, to reiterate, the strike is not made in order to avoid something, a deterrence before the enemy strikes. It’s also very different to the twentieth century logic of the balance of threats or prevention. Rather, what happens in the present is based on a preemption of the future, and of course this is also linked to what has been called a tendency towards premediation in the media.

Another everyday example of this new speculative temporality discussed a lot nowadays is preemptive policing. You have it in science fiction, notably with the “PreCrime” and precog detection of Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report (and the Spielberg film based on it). Versions of this are adopted more and more in policing today. This has to be distinguished from other current surveillance strategies; for example, CCTV is more of an older idea of watching what people are doing or documenting what they have done, to reinforce exclusion mechanisms. The question today, if one puts it in chronological terms, seems to be more along the lines: what kind of policing is needed to apprehend people even before they do something, with what they will do — as if the future-position promises more power, which creates a future-paranoia? This is less a surveillance directed to the exclusion of people than one that deals with people inside the social space, with the value they produce. How can they be observed and how to extract value from their activities? There is of course a hugely important biopolitical factor in this regulation of the population, especially with regards to medicine and insurance.

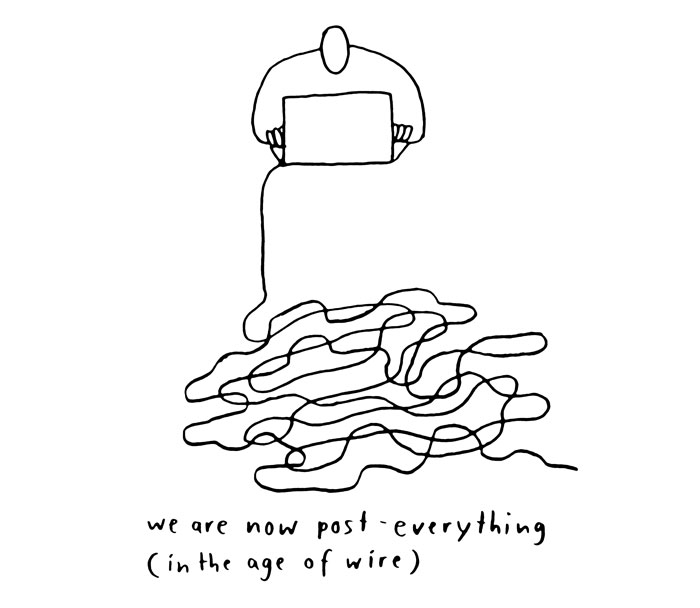

SM: Along with “pre-,” what’s advanced by the time-complex is also a condition of the “post-,” the current ubiquity of which characterizes where we are at now, and which is maybe added to with the contention of the post-contemporary. Everything now seems to be “post-” something else, which indexes that our understanding of what is happening now has some relation to but is also disconnected to historically given conditions.… While the “pre-” indexes a kind of anticipatory deduction of the future that is acting in the present — so that future is already working within the now, again indicating how the present isn’t the primary category but is understood to be organized by the future — what the “post-” marks is how what’s happening now is in relationship to what has happened but is no longer. We are the future of something else. The “post-” is also a mark of the deprioritization of the present.

If we are post-contemporary, or post-postmodern, post-internet, or post-whatever — if we are now post-everything — it is because historically-given semantics don’t quite work anymore. So, in a way, the present itself is a speculative relationship to a past that we have already exceeded. If the speculative is a name for the relationship to the future, the “post-” is a way in which we recognize the present itself to be speculative in relationship to the past. We are in a future which has surpassed the conditions and the terms of the past.

Combined, the present is not just the realization of the speculative future (the “pre-”) but also a future of the past that we are already exceeding. As many contributors to this issue propose, we don’t quite have the bearings or the stability or the conventions that the past offers to us (the “post-”).

AA: That’s the important thing, that the change of the present, the shaping of the present, is not necessarily determined by the past. The present can no longer primarily be deduced from the past nor is it an act of a pure decisionism, but it’s shaped by the future. For me, that’s the key problem and the key indication that the logic of the contemporary with its fixation on the present — you called it the human fixation on experience — that this presentism has difficulties or even completely fails in dealing with the logic of being constituted by the future.

I think that’s partly the reason for all the critical reasoning and questioning of contemporaneity in recent years that happened parallel to the so-called speculative turn. Unfortunately, speculation is often discussed as just a logical or philosophical issue but not in its unique time aspect. But obviously we are also still looking for the right philosophical or speculative concepts for this post-contemporary (or past-contemporary) condition or time-complex.

SM: Yes, as much as we are each indebted in different ways to speculative realism, and shared the move away from the poststructuralist or late-twentieth century models of philosophy that we both come from, nonetheless speculative realism has mostly argued for an intra-philosophical or conceptual notion of speculation, which is to think of the outside of thought and the experience of thought. The interest of the post-contemporary is to understand and operationalize the present from outside of itself. I don’t know at this point if that is also outside of thought. But, in any case, the time-complex can be thought, with “speculation” taken primarily as a time-historical speculation, like futurity, rather than an exteriority to experience or an exteriority of thought. This brings us much closer to current business and technical operations rather than the conceptual demands of speculative realism.

Operationalizing the Speculative Time-Complex

SM: One instructive manifestation of the operationalized speculative time-complex are derivatives. Of course, derivatives are now key to speculative finance, and they are “speculative” in that they use the unknown future price of an asset and the risks involved therein to draw profits against a present price. As Elena Esposito shows really clearly in her contribution, with derivatives the uncertainties of the future are used to construct prices in the present and this scrambles the standard time structure of past-present-future. The derivative is a clear example of how profits are not extracted on the basis of production or from fixed capital like equipment, plant and construction, all of which depend upon the history of investment, nor from variable capital like labor or wages. These belong to traditional industrial models of accumulation, in which a factory is built, workers are employed and paid, materials are used at a certain price, a product made or grown, then sold at a higher price than the costs, and profits made. All of which means that the profits are accrued from production that has happened in the past and subsequently exchanged on the market. The exchange of the product is the completion of a sequence that must have already happened. With the derivative model, on the other hand, a price in the future which is yet to happen is anticipated, and it is this future eventuality which is unknown that is operationalized to extract profits — on the basis, to reiterate, of a future that is unknown and unactualized.

Derivatives are, in Natalia Zuluaga’s phrase, a specific kind of future-mining, an extraction from the future in the present. But this mining of the future in the present changes what the present is. The present isn’t the one that you started with. The very construction of a speculatively constituted present — the “pre-” — actively puts the present into a past that it also is, the “post-.” There’s one version of this configuration that you and others have described through pre-emptive policing, pre-emptive strikes, pre-emptive personality and so on, which are also anticipated through big data, and the use of algorithms through consumer information. But it also differs from the logic of preemption where, taking the example of a preemptive strike, you eliminate a possible enemy in order to prevent what might have happened — but which also may not. It’s rather that your act — price setting in the case of derivatives, but the construction is generalizable — is itself modified because you take this very proximate future into account as a condition of the act that should then be made. The future is acting now to transform the present even before the present has happened. As Esposito argues, it is not only the linear schematic of time that is scrambled, but also the very openness of the present to the future.

But aren’t these conditions just what you and Anke Henning were also dealing with in your Speculative Poetics project, be it more in relation to formal literary and linguistic analysis?4

AA: Anke and I wanted to problematize certain initial assumptions, such as the very easy and oversimplified tension between speculative realism and poststructuralism. You and I also sought to rework that opposition with the essays collected in Genealogies of Speculation, which looks to vindicate a speculative dimension in the philosophy of the last decades.5 But, in particular, Anke and I explored how a prehistory of the current speculative philosophy took up the idea of speculative temporality.

SM: One of the things you and Anke do in Present Tense, which is really important to emphasize here, is to introduce grammar structures within language as a kind of time-complex. Language for you seems to be a cognitive, plastic and manipulable medium of the time-complex.6

AA: Language has one unique and key feature in this regard: a tense system. The tense system is really important to our understanding and construction of time, even more fundamental than the experience of time because it structures that experience — though not in a relativist sense. Most continental philosophies of language or time actually don’t deal with what is specific to this system because they don’t really focus on the grammar. It’s a problem with phenomenology as well as with a lot of deconstructivist and post-structuralist philosophies. What is more instructive than those traditions has been analytic philosophy and non-Saussurean linguistics. For example, John McTaggart and Gustave Guillaume think a lot about sentences like “every past was a future” and “every future will be a past.” These basic structural paradoxes — or apparent structural paradoxes — can be tackled via an analysis of grammar. There are some important technical issues here that I had better not go into—

If we are postcontemporary, or postpostmodern, postinternet, or post-whatever — if we are now posteverything — it is because historically given semantics don’t quite work anymore.

SM: Yes, maybe later. The core point seems to be that formulations like “every past was a future” and “every future will be a past”—

AA: And so on: every present as well—

SM: That’s what I was going to say: what’s very relevant about those two formulations for the identification of the speculative time-complex that we are here calling the post-contemporary is that they articulate a time structuring in which the present drops out. So determinations of time can be established that don’t require the present as their basis. The tense structure of language allows for that, formulating the non-necessity of the present as a structuring condition of the tense structure.

AA: And what struck me as necessary for speculative realism or any kind of speculative philosophy was a better understanding of what I would call a speculative and materialist temporality. For Anke and me, this meant understanding time on the basis of the grammatical structures of language — language understood as something material — and to develop not a time-philosophy but rather a tense-philosophy.

SM: At the same time, you make the criticism that speculative realism, as we mainly have it, doesn’t take ordinary or literary language seriously enough because it consigns it to correlationism — meaning, effectively, the dimension of human experience that never leaves itself.

AA: Yes, but that’s their self-misunderstanding.

SM: And why did you call it speculative poetics?

AA: Because our work also implies a polemic against aesthetics and the general focus on aisthesis [perception] in modern philosophy; and, to return to your earlier point, also against the primacy of experience.

SM: By “constructive,” do you mean that tense can be operationalized in order to structure time differently? The sentences formulating that the past was the future and eclipsing the present are not just descriptive. They also construct time relations within language, especially through narrative. Does the same operationalization of tense happen outside of human languages, for example through the derivative structures we mentioned?

AA: The point is rather that “experience” of time and the construction of something like chronological time are only effects of grammar, not a representation of the direction of time or of what time really is. It’s the tenses in language that create an ontology of chronological time for us, and we live this time as the illusion of having a biography.

SM: Isn’t this limitation of consecutive ordering what the speculative time-complex surpasses? What we have with the speculative time-complex is that the future, which includes the future we don’t know, gets included within the current reckoning and the present is coming disconnected from the past. The dismantling of the linear ordering and the primacy of the present equalizes past, present and future.

AA: Absolutely. Some of today’s fiction and, more precisely, present-tense novels are far more dangerous than traditional narrative in really forcing time out of joint. As the result of 20th century vangardisms, present-tense novels subject readers to a speculative somatics of time. Maybe A.N. Whitehead would call this mode of sentience “feeling.” This time does indeed “feel” hallucinogenic, haunting, urging, hyperstitious, horrific, as David Roden shows in his contribution to this issue. In short, one feels time’s power coming from the future. In the most radical case this speculative feeling makes you change your life. Becoming on a par with the future you have speculated initiates a metanoia. But this goes very far…. The temporal phenomenon we were interested in is how all the aesthetic understanding of literature doesn’t understand that the present tense produces asynchrony.

SM: Asynchrony?

AA: That the present is not fully experienceable but is split in itself, and that tense structures can actively operationalize this splitting. It is laden with innumerable past-presents. It presents actual phenomena as post-X phenomena and it desynchronizes time.

Left and Right Contemporaneity

SM: This comes back to what we were saying earlier: that the future itself becomes part of the present. This could be taken as an extension of the present without a future radically distinct from it. And it often is, with the leftist-critical claim of the loss of futurity under the capitalism of complex societies. That is the fundamental limitation of contemporary leftism that Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams have identified, and which they look to countermand with their specific determination of what, in their contribution to this issue, they identify to be “a better future,” which provides an active horizon to direct the politics of the present.

AA: I think we have a slight disagreement on the current state of neoliberalism, which you define as a state-business nexus directed to the concentration of capital and power, which requires and consolidates increasingly autocratic elites. I tend to think that we are already going past this stage. For me and others, neoliberalism is a move toward something one can call financial neofeudalism, in which key columns or foundations of the political economy of capitalism — like a safe nation-state, a governed population and a market regulating itself, or other basic economic assumptions like economic recovery or growth leading to more jobs or higher profits leading to greater competition instead of monopolies or oligopolies etc. — have started to disappear, and we are now in a fundamental financial and social crisis, with increasing depth of inequality.

But instead of debating whether we are at a new financial feudalism or just another stage in capitalism, let’s instead focus here on the basic hypothesis we are jointly proposing: given the social, technological, and political transformations since the 1960s and 70s that we’ve already mentioned, and which are also embodied in contemporary art and in literature with the emergence and consolidation of the present tense novel in the period since, we live in a new, speculative time structure. There have been basically two responses to this transformation. On the one side, there is a right-wing or reactionary countermanding, looking toward the past as a kind of counter-balance against the negative aspects that everyone observes and feels: the frustrations, disadvantages and mistakes of neoliberal financial neofeudalism. The other standard response to the speculative time structure is the left or critical one, which is also the prevalent one in contemporary art. The focus here is not the past as a place of semantic security but instead on the present as a site or condition of resistance against the change to a speculative time.

Yet, for all the contentions between left-critical and right-reactionary responses to the emergence of the neoliberal mobilization of the speculative time-complex, both are just playing in different ways into the hands of this new formation of neoliberal capitalism, or financial feudalism. It’s perhaps more obvious with the right-wing reactionary tendencies, which in no way disrupt but rather reinforce power structures that enabled the new social, economic, political formation. However, with left-critical reactions too, there is a kind of suffocation, to the extent that most people have the feeling of not being able to gain traction in the present, to change something, and to have something like a future worthy of its name. Contemporary art is both a symptom and surrogate of that futurelessness, with its constant celebration of experience: aesthetic experience, criticality, presentness and so on.

SM: That is an instructive formulation of typical left and right reactions, and typical defensive moves around the emergence of the speculative time-complex and the loss of bearings that it institutes in relationship to both the past and the future. Though there are many ways of understanding or setting up a relationship to the speculative time-complex, what the right does is to simplify it, to reduce it as a complex, and to recenter it on the present as the dominant moment on the basis of tradition. The right has always done this in modernity: if modernity is a paradigm in which the new happens in the now, what has characterized the right is a defense against the emergence of the new as the basis for actions, social organizations, aesthetics, meaning and so on. The authority of past conditions is invoked as a stabilization mechanism for modernization. To be clear: the right is not necessarily against modernization but stabilizes its disruptive effects by calling on what are then necessarily conservative or reactive historical formations. And faced with the operationalized speculative time-complex of neoliberal capitalism, in a way the right can carry on doing what it has always done without necessarily recognizing that what it is reacting against is no longer the modern but a new condition.

The Rightism of neoliberalism makes sense on this basis: even though I disagree with the adequacy of the phrase “financial neofeudalism” to describe what is happening in capitalism, it nonetheless serves to capture the increasing autocracy that goes along with the neoliberal restructuring. The political question then is how that autocratic, post-democratic kind of power is to be legitimized. Those on the right are very useful just here because what they endorse, essentially, is the authority of a recognised historical or elite formation that stabilizes semantics — and perhaps only semantics — in the newly established conditions.

AA: And the left-critical abreaction?

SM: In a way, leftism makes the problem of “the contemporary” more evident because the left in its progressive forms has been attached to modernism. The now in which the new takes place is the fetish of change for the progressive left, exemplified by its revolutionary ideals and clichés. The left’s abreaction to the speculative time-complex is to retrench the present as the venue or the site for thinking about and confronting the reconstitution of social and time organization, and semantic reorganization too. Instead of seeing the future as condition of the present, the present is instead taken to extend out indefinitely and cancel out the radically different future (the revolution, notably).

But the speculative present as we are identifying it is, by contrast to this leftist melancholy, the entrenchment of the future and the past which folds into the present, in a way that certainly deprioritizes it and maybe even makes it drop out — as in the phrases demonstrating tense structures we discussed earlier. The past was the future, and the future will be the past.

AA: There is no critical interruption from the present in this speculative present.

SM: No, it’s constructed by the uncertainties of the future and the absence of the past.

AA: That’s why the left-critical thinking of the event or the emptiness or openness of the present — of contemporaneity — is still vestigially modernist. And, as Laboria Cuboniks remark in their contribution from several different angles, it’s not adequate to the tasks and conditions of the twenty-first century.

SM: What the left sees in the speculative complexification of time is an extension of the present rather than its thinning out by the forcing of the future or the disestablishment of the past. Historical, futural, anticipatory relationships are maintained with an emphatic insistence on the presentness of action, aesthetics or experience. This is insistence on “the contemporary.” It is still premised on the present as the primary tense. And what happens with the emphasis on contemporaneity is a determination of the present as indefinitely extended. The contemporary is a time form that saturates both the past and the future, a metastable condition.

A leftism still attached to modernism won’t have traction on the speculative present, even if that leftism is more attentive to the time-complex than the right because it’s not trying to restore a past (though its revolutionary wing does seem largely interested in restoring a historical semantics, while its social-democratic wing now maintains an interest in failed market solutions). Even if it’s accepted that the left is more open to modernity than the right (which is questionable outside of the left’s self-reinforcing phantasm), it holds that the present extends into both the past and into the future, which supposedly destroys the future as a future. And, as Esposito remarks in her contribution, it doesn’t see that what it is actually involved with is the future now. That today is tomorrow, as you put it in another occasion.

AA: It was “Tomorrow Today.”7

SM: Exactly. That title indexes how the speculative present is in a pre-post formation, or post-contemporary. The present now is not the time in which the decisions are made or the basis for the new, as it was in modernism. The new is happening instead in a transition between a past and a future that is not a unidirectional flux, but a speculative construction in or from the directions of past and present at once.

AA: The whole idea of what in German is called Zeitgenossenschaft — the contemporary, more literally, “comrade of time” — is problematic because it far too often signifies the wish to change the present completely with an insistence on the present. The contemporaneity of Zeitgenossenschaft indicates the idea of having traction in the present by getting closer to it, and that is no longer adequate to the task. It is simply the wrong way to think. What is needed instead is neither Gegenwartsgenossenschaft — comradeship of the present, nor Vergangenheitsgenossenschaft — comradeship of the past, but rather a Zeitgenossenschaft from the future (die Zukunft), a kind of Zukunftsgenossenschaft. We need to become comrades with and of the future and approach the present from that direction.

An Aesthetics of Everything: Contemporary Art Contra Futurity

SM: Under the guise of the contemporary the modernist left has a kind of melancholia for a future that it cancels to preserve its received premise: the present. The past and the future are taken as modifications of the present. The advantage for left-criticality is that the contemporary can then accommodate, dissimilate, colonize all of time in its own terms. This is really evident in contemporary art, which becomes a kind of last word in art. It cancels even its own futurity if not the future in general for the sake of its own critical accomplishments, which are of course capture-mechanisms demonstrating contemporary art’s salience to everything.

AA: Contemporary art is a good example also because it has not been just a victim of the recent economic and political reordering of neoliberalism, but has really helped build the matrix of that reorganization by implementing its logic on all levels from a left-critical angle. Specifically, it has stressed the dominance of the present or the past as condition for action, and also, as we said before, individuated experience as the main benefit of that reorganization. It takes the lead in a general aestheticization at all levels: personal/individual creativity, originality etc; environment and cities as spaces of creativity and “disruptive” entrepreneurialism; the conflation of production and consumption with the prosumer, whose “natural” habitat is, precisely, the smart city itself turned into a kind-of continual biennial event. All of this goes back to the fetishization of presentness and of the aesthetic experience of everyday life at the expense of its reconstruction, which would be the task of poiesis or a poetics.

SM: Via the continued enrichment of experience through an aesthetic encounter, contemporary art also draws attention to specifics and particulars at the cost of systemic understanding. Victoria Ivanova draws attention to this operational logic in her contribution to this issue, linking it to the human rights regime as a kind-of counterpart in global ordering that constructs the relation between universality and particulars after the so-called “end of history.”

Let’s be clear that this is not a condition of stasis: contemporary art is integrated into neoliberalism’s enrichment of experience for its elite beneficiaries, and those thereabouts, in a way that promotes change and revision. This is part of the complexity of the speculative present of neoliberal capitalist development: it looks like a personal good, an enrichment of experiment by aestheticization, by promoting change while maintaining a certain stability —

AA: An aesthetic experience not just of art, but of everything.

SM: Yes, the aestheticization of experience, or experience as an aesthetic. That is also a generalization of ethics too: the appreciation of differences without political demand, a kind of superliberal —

AA: De-politicization…

SM: A de-politicization because it’s a de-systematization. Such an aesthetic/ethical appreciation is a repudiation — indirectly made, as a kind of background condition — against making systemic determinations. The latter are held to be too complex to be apprehended or reworked, impossible or just wrong-headed because totalitarian. What we are obliged to be restricted to are instead only the singularities of what is and of experiences. That is certainly the injunction of contemporary art, operating via each artwork and its social norms. And to that extent it is a minor but paradigmatic model for a neoliberal sociality, as Ivanova remarks.

The way in which contemporary art becomes a plaything for big power in neoliberalism, despite many of art’s critical content claims against that model of domination, this convergence makes coherent sense on this basis. But what needs to be emphasized here is that rather than just remaining at the level of the conflation of varieties of anarcho-leftism in contemporary art’s critical claims with the rightist interests of increasingly concentrated capital and power, the two can be seen to have common interests in flattening out or simplifying the speculative time-complex, as reactive detemporalizations of the speculative present.

What is necessary against these and other such reactions is to have strategies and praxes — and that means theories — to gain traction in the speculative present. And that is what both right-wing conservative strategies and left-critical or aesthetic approaches are utterly incapable of doing. As we’ve said, both are combined in contemporary art which is then also incapable of doing anything but consolidating this condition, no matter what it claims to do, what it pretends to do, or what its content claims are.

AA: We agree that we have to think and act within a post-contemporary speculative time-complex. But now the question is: how to differ from the capitalist or financial-feudalistic version of it? How does a speculative theory introduce a difference into the speculative present from its exploitative formation by neoliberalism, however else we might characterize that form of domination? What would be a speculative politics capable of accelerating the time-complex, in the sense of introducing a difference to it?

SM: That is the fundamental political question, for sure. One further theoretical point might help us understand the difficulties here. Namely, why is our wish to get past contemporaneity not just Jacques Derrida’s criticism of the metaphysics of presence? For Derrida, presence is the primary category of western metaphysics, circumscribing not just the main philosophical doctrines in the Western tradition but also correlative prevailing social, political and language formations. And Derrida proposes that the present held to be adequate to itself needs to be dismantled and reconstituted. For him, the task is to deconstruct presence — ontologically, in time, space, and so on. We are contending that that contemporaneity is no less an extended social historical present, presentification. So, in a way, aren’t we just doing Derrida again, even though he is a key figure in the critical lineage that needs to be surpassed?

AA: It’s not the worst thing to be repeating Derrida to some extent. But with his deconstruction, it’s a necessarily ongoing process of the ideology or effect of presentness establishing itself and also being deconstructed: Metaphysics needs to be deconstructed and it deconstructs itself all the time, so it’s an unending procedure. Unfortunately, this goes down all too well with a tedious modernist aesthetic of the negative, not so far away from the fetishes of Frankfurt School, of the non-identical, or of a “différance” that plays with the opposition between meaning or content, traditionally the bad thing, and subtraction, which is the good thing, as are emptiness and non-readability. And I think that’s a very modernist, twentieth century logic, and also the logic of the contemporary. Contrary to all such attempts, the reworking of the speculative present must admit that meaning is always there anyway, and the constant procedure of changing and subtracting it endorsed by Derrida and the lineage of critique he belongs to is not necessarily something positive.

So, with deconstruction and most other strands of last century’s aesthetic philosophy, whatever its other merits are, you end up in an aesthetics that is an ongoing celebration of the gesture of interruption, of emptying out, and so on (just think of some of Badiou’s tedious disciples). But with the speculative time-complex we are no longer in that logic of interruption. I don’t have a problem with an ontology of time, as long as it gives us another possibility of understanding time than via the present.

SM: You are right to say Derrida ends up in an aesthetics. But it is also an ethics, with its emphasis of an always singular and irreconcilable experience of vulnerability. He rails against established meaning.

AA: We should not be afraid of establishing meaning. On the contrary.

SM: Certainly. I don’t know if my additional observation is compatible with your response, but it’s that the construction of the speculative time-complex is the societal — meaning mainly technical and economic — operation of the deconstruction of presence. That is, the way that semantics or instrumental operations are occasioned in time-complex societies is precisely the deconstruction of presence and meaning in the way that Derrida affirmed. We are then no longer in a metaphysics of presence because of the speculative time-complex. Derrida speaks to this somewhat in his discussion of teletechnologies and the displacements of space, locality, and ontology that are involved.8 But the politically difficult and mostly evaded point in these discussions is that the sought-after deconstruction of time, meaning and so on are actually taking place though processes of capitalization. The “they” of the state-business nexus effectuated that deconstruction, and they did it better than Derrida. In this light, what “the contemporary” enforces is the retrenchment of presence against its deconstruction by the speculative time-complex. Contemporaneity here includes all the procedures of interruption, subtraction, delay and non-identity you mention, as well as many others including semantic deconstruction.

Grammar of the Speculative Present

SM: To return to your question: in contrast to the sorry complex of right and left reactions to the speculative present that is contemporaneity in art and elsewhere, what is needed is a way to engage with the time-complex that is not just about drawing profits and exacerbating exploitation on this revised basis, as neoliberalism has so successfully done. That capitalized formation of the time-complex is a kind of limited and restricted organization of the speculative present; one that for all of its complexity reverts to presentification because the profits have to be accumulated now as per the short-termism of neoliberal capitalism.

AA: The problem is that one has to admit that the social, technological, political and economic formation of neoliberalism has an advantage because it acts within the speculative temporality, in part as it has established institutions functioning in accordance with this speculative logic. But the neoliberal formation also reduces the speculative dimension of the time-complex because it repudiates the openness or contingency of the future as well as the present.

SM: No, I disagree. I think the problem precisely is that it opens up more societal and semantic contingency. That is what Ulrich Beck and others involved in the notion of “risk societies” diagnosed in the 1990s in other terms.9 What they call risk is the acknowledgement in the present of how the speculative time-complex opens up the future as the condition for a societal order (more accurately, a quasi-order).

AA: No, no. The contemporary is a constant production of innovations and differences, but it doesn’t introduce a difference to the recursive movement of time. The German allows for distinction between Beschleunigung, which is acceleration as a speeding up, and Akzeleration. The latter really means something like, in the old days, when a clock was too fast. A deviation ahead — not a circular movement, but a recursive one. Akzeleration introduced a kind of difference to the functionality of the clock. And it’s this difference that the neoliberal or neofeudal economic system hardly allows for, because it produces an automatized future. While the kind of criticism typical of the contemporary (left) art is not wrong, it doesn’t see the possibilities of speculative time and reduces it to the present. It just sees the capitalist effects of it. Contemporary critical art mostly produces different — essentially, decorative — objects or meanings that maintain the reduced form of the speculative time-complex. And I am arguing not on the level of just semantic meaning, but really on the level of the materiality of language and the materiality of time, which are not separable.

SM: So the task of the post-contemporary against contemporaneity is to change time?

AA: The post-contemporary works within the speculative present. It understands it, it practices it, and it shapes our temporality. Are there alternative actualizations of the speculative or asynchronous present, are there different readings of it? In her contribution, Aihwa Ong highlights some of these constructions in her anthropology of what she calls “cosmopolitan science.” She outlines how the universalisms and abstractions intrinsic to scientific entrepreneurialism support and are supported in Asia by specific historical-culture formations of meaning, scrambling any simple opposition between local and universals, or between past (culture) and future (entrepreneurial technoscience). With speculative poetics, to take another example, the issue is how do we understand the future in an open way and not just as a kind of indicative future.

SM: What do you mean by “indicative”?

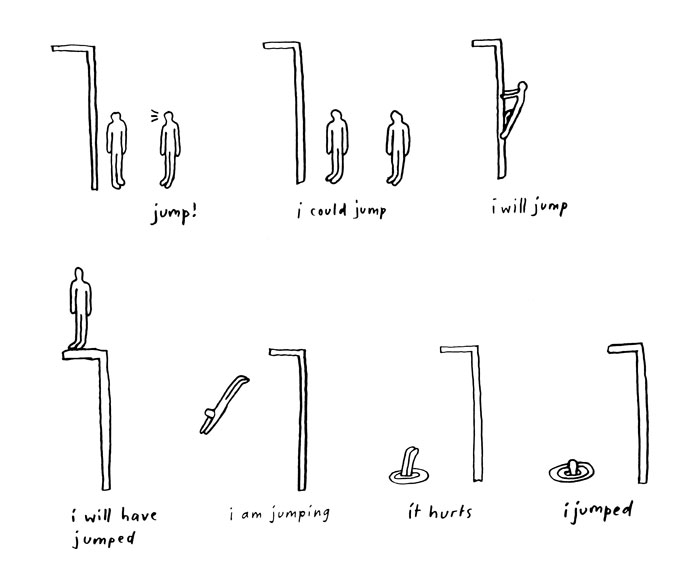

AA: There are three modes in grammar: the imperative (“Go!”), the indicative (“She goes.”), and the conjunctive (“I could go.”). In language philosophy — but also politically — it’s important to understand that all tenses are modal. The past and the present have to be understood in a modal way — primarily as indicative. But the future tense and the conjunctive mode are pretty close in that they both deploy the grammar of possibility. It is this contingency that is reduced by the logic of the contemporary logic and is often misunderstood by the closure of speculative time to the present (“I will have gone.”). But, if I may get a bit more into the technical analysis, the conjunctive is constructed before you are actually going, so whether you are using the conjunctive mode or the future tense in the present you are not yet going. Maybe that’s too technical for here, but the main point is that mode is how a future tense is transformed into a present tense and subsequently into a past tense.

SM: Is the conjunctive the form of contemporaneity? What it sets up is a sense that actions could have happened, but did not happen: “they would or could go,” but they didn’t. And this is a sense where the subject of the sentence is left with a potentiality, which is unrealized.

That makes sense of the celebration of “potentiality” everywhere across the critical left today, and also, again, the limitation of the speculative time-complex by the domination of the present. Claims in contemporary art and contemporaneity are emphatically limited only to setting up options with potentials, without actually doing anything or mobilizing the speculative present to construct a future. The future is only and just a set of potentials that must never be actualized for fear of instrumentalization and, paradoxically and self-destructively, realizing in any present a future radically distinct from the present.

AA: The reduction of the time-complex to contemporaneity does not understand the future to be contingent but the only possible future present that becomes real; in grammatical terms, the future or the present here are understood only via the indicative. But the present is not just an “is,” just as tenses don’t represent time. We have to get rid of an a-modal understanding of time.

SM: The contemporary is a-modal?

AA: Yes, and what is needed instead for a thinking and praxis adequate to the speculative temporality we live in — a Zukunftsgenossenschaft as I called it earlier — are means for transforming a future tense into a present tense. That’s why for me grammar is a way of understanding speculative time in its openness, instead of subjecting it exclusively to the indicative mode. A future happens in the present only if a conjunctive is successfully realized, which happens by way of an imperative. In between “I could go” (present tense conjunctive) and “I go” (future tense indicative) is the hidden command “Go!” (imperative).

For me, it’s exactly this grammatically organized difference that opens up not just a different future and the possibility to do and act differently in the present instead of being subjected to an automatized future, whether it’s by preemptive policing or derivatives. More generally, we have to understand that language changes meaning and time — and on a material and ontological level, not just on a linguistic or conceptual level. These complexes can be tackled via grammatical analyses.

SM: OK, but as nearly all the contributions to this issue demonstrate, we also need to generalize the construction of the time-complex beyond language and its grammar. The conditions we are talking about are made of the broad infrastructures and systemics of the speculative present in large-scale integrated societies. Esposito identifies a scrambling of the time-line against its received and modernist logics that suggests a new openness to the future, which is to the advantage of a relatively new kind of capital accumulation but can be mobilized otherwise. Ivanova makes the case for how a new global juridico-political quasi-order is constructed via unstable restagings of the relations between particulars and universals, while Srnicek and Williams look to the systemic techno-social advance of robotics and automation to transform the fundament of the capitalist rendering of human activity. Benjamin Bratton extends these possibilities under the rubric of “Speculative Design” to more specific scenarios and, simultaneously, along longer time-lines; Ong also takes up the jurisdictional and operational issues in the specific case of the fabrication of a scientific enterprise that makes sense in ethno-cultural terms in Asia, transforming the practical manifestations of where and how identity formation takes place. Laboria Cuboniks wrestle with the legacies of feminism given just such futural and technoscientific reorganization of bodies, identities, and concepts of selfhood; and Roden scrambles body, affect, language in light of a “Disconnection Thesis” according to which the kinds of intelligence inaugurated by Artificial General Intelligence completely change the space of coding at any and every order.

In general, and similarly to the insufficiency of experience as a basis for apprehending the speculative present, the constructions of (presumably only some) human languages is only part of this integrated complex but not wide enough as a mechanism to meet the broad material and semiotic condition.

AA: We need more than a language theory, for sure, but in any case we need what I call a “poetic understanding” which, for me, is informed by language theory instead of an aesthetic one.

SM: My divergence is that, first, even taking poetics as a name for production in general, it still seems to me to be too tied into the structures and affordances of more or less ordinary human language and their ordering. That’s of course a fundamental condition of the systemic, social, technological, economic structuring and mediation necessary for large scale organization. So, while poetics as you present it gives us as human linguistic actors a way of reordering the speculative time-complex in other formats than the kind of repressive mechanisms of contemporaneity and what you identify as the indicative, it’s also necessary that the restructuring are operationalized also in non-linguistic terms. We have to open up the time-complex in its infrastructures which are more structured in terms other than those of human languages. This is what Bratton’s proposal of Speculative Design in this issue puts forward in concrete ways and with specific situations and time-lines, not least with his identification of “The Stack,” which rearranges sovereign power according to the material and infrastructural conditions of computation that is interconnected at a planetary scale. Even more generally, however, we need a grammar adequate to the expansive infrastructure of the time-complex in its widest formation.

Revised transcript of a conversation held in Berlin, 29 January 2016.

Illustrations Andreas Töpfer

1. The time-complex is specific to the structures of integrated sociotechnical and psychic mnemic systems of individuation proposed by Bernard Stiegler. See for example Technics and Time Volume 2: Disorientation, trans. Stephen Barker (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008) and Symbolic Misery Volume 1: The Hyperindustrial Epoch, trans. Barnaby Norman (Oxford: Polity, 2104). But the speculative time-complex is distinct to Stiegler’s thesis in that (i) it comprises a speculative constitution of time rather than memory and human temporalization, and (ii) the speculative time-complex is here affirmed against Stiegler’s appeal to rescuing an aestheticallyconstituted experience of individuation despite complexifying sociotechnical configurations.

2. Rob Horning, “Preemptive personalization,” The New Enquiry (September 11, 2014)

3. Brian Massumi, “Potential Politics and the Primacy of Preemption,” Theory & Event 10:2, 2007.

4. See here.

5. Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik, Genealogies of Speculation (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

6. Armen Avanessian and Anke Hennig, Present Tense. A Poetic (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

7. See here.

8. Jacques Derrida and Bernard Stiegler, Echographies of Television: Filmed Interviews (Cambridge: Polity, 2002).

9. Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (London: SAGE, 1992).