Introduction

HOSTILE TAKEOVER

Sneakers instigate revolutions, condos promote freedom, and the “sharing economy” has become a means of revolt. Whereas shifting the fulfillment of every desire onto the market is no new phenomenon, perhaps the shrinking of the collective political imaginary into ever-more circumscribed, individuated, and personalized units may be. Also the unprecedented pace at which inspiring images and ideas are rapidly circulated, shape-shifted, and cast off could similarly be described as a defining feature of our cultural present.

A range of prominent thinkers, political actors, and cultural producers were asked to consider the analytical implications, political consequences, and artistic reverberations of corporate culture’s nimble appropriation of leftist, oppositional, and utopian ideas. They were given a range of questions about the specificities, effects, and historical durée of this reverse appropriation and asked to consider which alternative cultural strategies, if any, might still be viable.

This line of questioning tends to bring out the malaise of art’s relationship to its own price point and its undeniable flirtation with the old aesthetic suspect that is spectacle. Viewpoints range from acknowledging subjects and modes of uncommodifiable resistance to asserting that no signifier is safe from appropriation in our digital times, in which signifier and signified are subject to unprecedented entanglements. In sum, this conversation produces a mood poll of whether and where there may still be such a thing as collective feeling—or a capacity for a slow politics even—that is worth banking on.

Sarah Lookofsky, General Advisor BB9

A questionnaire was answered in the form of a statement, in part, or in its entirety by the following participants:

Tyler Coburn

Does a cooptation of oppositional or left political ideas, phrases, and images by capital weaken or even empty these ideas of their political significance, radicality, and potential? What do you think are the psychological and social effects of this persistent stream of neoliberal broken promises?

To answer the question simply: Yes, absolutely, of course.

But to answer at greater length (with the U.S. context in mind), we must ask: Which “left political ideas, phrases, and images” are we speaking about? Those from Sanders-era Millennialism, Occupy, the anti-globalization movement, May 1968, or other lefts? Are all lefts interchangeable and thus equally susceptible to cooptation?

In asking these questions, I’m thinking back to Wendy Brown’s essay, “Resisting Left Melancholy,” which frets that “[i]f the contemporary left often clings to the formations and formulations of another epoch, one in which the notion of unified movements, social totalities, and class-based politics appeared to be viable categories of political and theoretical analysis, this means that it literally renders itself a conservative force in history—one that not only misreads the present but installs traditionalism in the heart of its praxis.” Written in 1999, Brown’s essay precedes recent American lefts, begging the question of how she would situate these waves. Nonetheless, her essay remains important in arguing that the contemporary left must break with precedent.

What might this look like in practice? Rather than persist as a passive object for cooptation, could the left willingly give up parts of itself to the neoliberal powers that be, thereby clarifying its commitment to others? Would the “psychological and social effects” of cooptation be less, if the left was complicit in this process? Obviously, this is a thought experiment (potentially, an ill-advised one), but any critical reformulation of the left, in the contemporary age, must consider how the forces of cooptation can serve, not impede, its cause.

The market’s appropriation of oppositional or counter-cultural ideas reverses artistic appropriation practices in which commercial communications are uncoupled from their intended logic and rearticulated to different political ends. Has the market’s increasing ease at appropriating artistic critique and left political imaginaries caused you to question or reconsider strategies of resistance?

I don’t think we can have a discussion about market appropriation without acknowledging the broader crisis of signification.

If we agree with Maurizio Lazzarato’s recent claim, then ours is increasingly a world of machinic assemblages and “asignifying semiotics,” wherein “man, language, and consciousness no longer have priority.” Algorithms, to give the common example, don’t care what a signifier signifies so much as how it figures into larger data trends. Therefore, we must disabuse ourselves of the idea that the shoe we search for on Google and the shoe that returns to stalk us in advertisement form, has anything to do with an actual shoe. It’s machinic assemblage in creeper form.

Given that much contemporary appropriation occurs through these asignifying processes, can we even talk of significance being stripped from something, in the classic sense? Are appropriation and détournement applicable terms, as each presupposes its object to possess semiotic value? Perhaps the best mode of artistic resistance actually lies in signification: in (re)assigning meaning to content of human provenance, handled without regard for its significance—and to the increasing amount of machine-made matter, generated in the absence of the sign.

Tyler Coburn is an artist and writer based in New York.

Eva Díaz

Gossip columnist Perez Hilton writes:

“Dutch supermodel Doutzen Kroes will be out of this world . . . literally. The new mom has secured herself a seat on board one of the first Dutch commercial flights to space, courtesy of Space Expedition Curaçao. Doutzen said of her upcoming trip: ‘My work has literally brought me to the most beautiful places on earth. But apparently nothing is as beautiful as the view of the earth from space. Astronauts, who have been lucky enough to have had that experience, say it is life changing. I cannot wait to go.’”[i]

The newest trend in luxury tourism is outer space.

What has been termed “New Space” exploration is emerging in the companies funded by tech billionaires such as Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, Mail.ru founder Yuri Milner’s Breakthrough Starshot, and Paypal cofounder Elon Musk’s SpaceX. These companies join British billionaire Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic in positing outer space as a zone for privatized, touristic exploration and capitalistic exploitation; to these men, access to space is an elite experience available to those who can afford it. And at $200,000 or more per trip, indeed only the very wealthy will enjoy the six minutes of weightlessness, and the covetable Earthrise snapshot, that these trips promise.

Who will serve the rich on these flights? Who will feed the models their fruit salads?

Outer space, where so few have actually been, remains a preeminent projective space in the leftist cultural imagination, the place wherein reside fantasies of rebirth, of reinvention, of escape from historical determinations of class, race, and gender inequality, of experiences of socially interdependent societies beyond the protection of the Earth’s atmosphere. The imagination of space itself frequently exceeds any known spectatorial experience, and is therefore a speculative political project in the sense that Frederic Jameson has described science fiction: “For the apparent realism, or representationality, of SF has concealed another, far more complex temporal structure: not to give us ‘images’ of the future—whatever such images might mean for a reader who will necessarily predecease their ‘materialization’—but rather to defamiliarize and restructure our experience of our own present, and to do so in specific ways distinct from all other forms of defamiliarization.”[ii]

If ever there is a moment to reassess the techno-utopian drive to exceed the envelope of Earth, now is that time. In particular, a reconsideration of the space age is taking place in contemporary art. Artists such as Jane and Louise Wilson, Connie Samaras, and Trevor Paglen have employed film or photography to explore the sites on Earth where older space programs once thrived, and to document new sites where private, corporate, or secret space programs are located. Other artists such as Mary Mattingly, Tomas Saraceno, Tom Sachs, Matthew Day Jackson, and Alexandra Mir are producing work, as R. Buckminster Fuller did, prototyping new possibilities for space travel and exploration, positioning artistic practice as a new kind of public science in which research and experimentation are made explicitly visible.

Yet unlike in Fuller’s work, many of these recent projects register an elegiac sense that the era of space exploration as a humanistic program of knowledge acquisition, interspecies communication, and even intergalactic colonization—in short, the epoch of cosmic optimism—has receded if not ended. Instead, these artists are concerned with how embers of dystopian millenarianism, already present during the Cold War period, are once again being fanned when libertarian New Spacers talk about an “exit strategy”: their plan to live off-planet if climate change becomes too brutal or political favor swings away from corporate neoliberalism toward economic justice and the equitable redistribution of resources.

We are in a threshold moment. Can we imagine and use outer space differently, not as an experience of economic privilege? Or will we allow it to be the privatized space many fear, where private wealth will stand in for the once public nature of national space programs—which though they emerged out of ideologies of manifest destiny and colonization, and the conquest and competition of military programs—were ultimately publically funded research projects? Reclaiming a space of leftist speculation requires a new imaging and a revolutionary new form of invention: a renewed space race.

Eva Díaz is Associate Professor in the History of Art and Design Department at Pratt Institute. Her book The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College was recently released by the University of Chicago Press.

[i] Perez Hilton, “Doutzen’s Going to Space,” CocoPerez.com (blog), April 14, 2011, http://cocoperez.com/2011-04-14-doutzen-kroes-flying-to-outer-space-in-2014. Last accessed on June 9, 2016. At this time there have been no space tourist flights in spite of the optimistic timelines proposed by these companies.

[ii] Fredric Jameson, “Progress Versus Utopia: or, Can We Imagine the Future?,” Science Fiction Studies 9, no. 2 (July, 1982), p. 151.

Jennifer González

For the most part, it seems that the market is ecumenical. As long as it can make a profit from selling, it appears not to care who does the buying. African customers are just as desirable as European customers, politically left customers are just as desirable as politically right customers, if they will pay the same prices, at the same rate. They are of course less desirable if they can’t. We can see capitalism’s “absorption” of radical, leftist, or anti-capitalist tactics, strategies and ideas as, for the most part, a way to expand an important market niche. It is not a new phenomenon.

Advertising does whatever it ideologically needs to do in the moment (i.e. reproduce racist stereotypes, promote luxury objects, “green” its corporate image). But perhaps it is also the case that some advertisers are ideologically sympathetic to “left” politics and are therefore using the available means to communicate their message?

What needs to be more carefully explored, therefore, are those moments when the market and capitalism are not politically ecumenical. It seems fairly obvious that the idea of the “invisible” hand or the “free” market is a convenient fiction. But it is sometimes less evident that large-scale market forces and capitalism have been allied with a racist and colonialist project from early on. The colonizing of indigenous labor, slavery, recent outsourcing, all demonstrate that it is impossible to separate capitalism from the history of racist exploitation. This is as true in wealthy as in economically disadvantaged countries.

Most artists recognize that they are already participating in “the spectacle” that is mass culture and in relations of mass consumption as both outsiders and insiders. All signifiers can be “appropriated.” What is potentially radical about art practice is that it can repurpose any tactic of signification available; what is potentially limiting about art practice is its conditions of display, its generally narrow audience. Left-leaning artists have been producing public, media-savvy, and fairly effective activist art for decades (think of Gran Fury, ActUP, Electronic Disturbance Theater). More recently, the artist groups such as Liberate Tate and Not An Alternative have been creating museum-based projects that work toward fossil fuel divestment. One of the stunning recent outcomes of this focused artistic engagement is that the Tate Modern in London did, in fact, drop its oil company sponsorship.

It is important to recognize that significant progress has been made over the past 100 years in terms of gender equality and decolonization, but it is slow going. At the risk of being somewhat iconoclastic, I would like to suggest that humans stop thinking in terms of “left” and “right” politics, religious frameworks, and utopian anarchies and start thinking only in terms of justice, equality, and sustainability. I am still in favor of labor politics and a critique of capitalism, but I also recognize that we need a more complex and comprehensive understanding of the forces producing racism, economic hierarchies, military violence, and planetary destruction before we can make productive, concrete changes.

Jennifer González is a professor in the History of Art and Visual Culture Department at UC Santa Cruz. She writes about contemporary art with an emphasis on installation art, digital art, and activist art.

Thomas Hirschhorn

Let’s start with one of the examples of a beautiful, critical, and powerful work: the work of Jean-Luc Godard. It is indeed a successful work, because he succeeded in creating a new form of cinema. His films give form to the artistic question: How can one produce—today, in our time—a work which reaches beyond its time, which resists historical facts? How can a work–beyond cultural, aesthetical, political habits–create a truth? And how can this truth become a universal truth? Jean-Luc Godard answers with the affirmation that art stands for absolute resistance. One can take his work and his position as an example. And I do. When Jean-Luc Godard says: “It’s about making film politically—it’s not about making political films,” it is something essential to me. Therefore I want to replace “making film politically” with “making art politically.” In my mind it is crucial to understand the difference between “working politically,” on the one side, and terms such as “political art,” “political artist,” or declaring oneself a “Political artist” or one’s work a “Political work,” on the other. The trap is to think or declare oneself a leftist, a “Political artist,” someone who does “Political work” because the problem is not about taking over the role and work of politicians and the goal cannot be taking a stand on the “good side.” We know there are leftist careerists, leftist opportunists, leftist content-providers. Therefore the real problem is not about content; the real problem is the form. The form must be powerful, critical, untamable, and the form—as such—must resist recuperation and appropriation. If this can be achieved, then we can speak about a Form as such. Giving Form, giving a leftist form means doing something new, doing something which transgresses, something which creates a breakthrough, something which goes beyond habits. I believe that the problem is to give a Form, a critical Form. A critical Form is a form that criticizes, but also that can be criticized, that is not established. Therefore, the artist has to pay a price for his form, this is what being leftist means: To pay for the Form! The leftist is the one who is ready to pay—primarily—for the Form. To pay means to be criticized, to be excluded, not to be invited. If not, it’s the trap of hiding behind a posture or a postulate—and it is easy then to be recuperated or appropriated. I am convinced that what counts—in the very end—is only “Form,” and this Form and the work which leads to this Form must be made politically. This means to work politically and to think politically. From this perspective I want to clarify the term “working politically”—and again—not just doing “political work.” To me, what counts, what makes the difference, is starting to ask oneself the important questions, the real questions, the big questions: Why do I think what I think? Why do I do what I do (art)? Why do I use the tool or instrument I use? Why do I give the Form I give?

Why do I think what I think? I think that art is universal. Universality means Equality, Justice, Truth, the Other, the One World. Art—because it’s art—can provoke a dialogue or confrontation directly, one to one. Therefore, I think that each human being can get in touch with art, each human being can be transformed by the power of art. I believe that art is the way to reinvent the world. Art is autonomous. Autonomy is what gives an artwork its beauty and its absoluteness. Art—because it’s art—can create the conditions of an implication, beyond anything. Art is resistance. Art resists facts; art is positivity, and intensity. Art, because it’s art, calls for equality. This is my conviction and my belief. Yes, I believe in art, I have faith in art, and I have faith in my work. Therefore I am ready to fight for it and for its position. Indeed, this is never a fight against something, but always a fight for something, for my work, for my position, for my Form. Working politically means—logically—being a soldier. A soldier with his own mission. A mission such as creating—with the work—a critical corpus and to work for a non-exclusive audience in order to establish new terms of art. I think that art is an inclusive movement. Art includes the Other, the uninterested one, the uninformed one. Art can reach Truth. Truth is not the verifiable fact or “true information,” rather Art affirms Truth. Belief in Truth is something essential. This means to work—and to think—politically.

Why do I do what I do–art? I understand art as a mission, a mission to accomplish—beyond success and beyond failure. To think in terms of “success” or “failure” in art makes no sense. Art can be an experience that doesn’t function, that doesn’t work. I learned from doing art that I can’t be the “disappointed” one, and have no right to be, and accepting such an unforceful discourse is obviously and definitely too easy. Doing artwork is not an escape or a dream. Equality is not given—I must fight for it, and can’t avoid the battle under the pretext of circumstance or today’s context. In order to stand up against inequality, I must allow myself Equality, I must authorize myself to assert being equal. Art enables me to assert and give a form to my own logic in a movement of self-authorization. Therefore to me, doing art is an emancipatory act and, as such, a necessity one—if I work in this dynamic I am working politically.

Why do I use the tool or the instrument I use? Working—as an artist—means understanding art as a tool, an instrument or a weapon to confront reality. I use the tool “art” to encounter the world I am living in. I use the tool “art” to live within the time I am living. I use the tool “art” because it allows a resistance to historical fact. I want to use the tool “art” precisely because it allows me to do an ahistorical work within the chaos and complexity of the moment. I want to use art as a tool to establish contact with the Other—this is a necessity—and I am convinced that the only possible contact with the Other happens “One to One,” as equal. I want to do a work that gives Form to the affirmation: The Other is included in “me” and in “I.” To love doing my work is already working politically, because the power comes—and must come—from Love. Art is a tool to keep the concentration focused on what counts to me, on what is essential—this means to work politically.

Why do I give the Form I give? The problem is to give “Form,” my own form, something only I see and something only I understand, something only I can give. I use the term “give Form” because it means giving from my own, giving Form is not “doing” or “making” a form. Therefore I invented my own “Form- and Force-field” to include the notions of Love, Philosophy, Aesthetics, and Politics. I always want to embrace these four notions in my work. Form is non-splittable, non-negotiable, and even, non-discussable. Form only exists as something entire, undividable, and complete, as an atom or a core, as hardcore—Form is hardcore. Form and Aesthetic are interdependent but are not to be confused. Form is what provides ethics, dynamics, and clarity in the incommensurable, complex, overcomplex, and chaotic world we are living in today. Aesthetics are the answer to the question: What does this Form look like? How is it made? What materials are used? Form never seeks a function, Form is never exclusive and Form can never be qualified with terms such as the “good Form.” To give Form is an act of emancipation, it is a resolution and a decision. To give Form—not to make form—means to work politically, because I have to give.

Thomas Hirschhorn is an artist.

Nina Power

I think that capitalism has no ideas of its own, being a machine for the generation of profit, and it is no surprise that what it does with creativity is to regurgitate thoughts and designs, and images in a profitable way. What does this mean for the production of thoughts, designs, and images under capitalism? An attitude of perpetual surprise that marketing will always recuperate ideas that the week before were dangerous to the state is naive (think, for example, of trainers in a window display a week after the London riots of 2011, marketed with the slogan “break these out” like a fire alarm). What are the options? One thing states and advertising companies loath more than anything is stealthiness, of communications they cannot immediately and visibly capture and repurpose. This is why terrorist networks and the cell model, as well as VPNs and people who do not use social media are a problem for both states and corporations, which increasingly resemble one another. I think there are modes of revolutionary subjectivity which cannot be captured, and there are also modes of religious subjectivity which cannot be commodified. There is always a limit to the recapturing: this explains why both the state and corporations are desperately operating at such a frenetic speed (think of the 24-hour courts following the English riots and the immediate and panicky upgrades to websites that corporations always make, even where no one wants them). We need a kind of revolutionary slowness that taps into existing forms of knowledge, much of which is not new.

The culture of the . . . all-too-undead New Labour project may be summed up in a single phrase: “Populism without popularity.” What does this mean? It means that the simulacrum of politics has overtaken any possibility of genuine social content, that the desire to be seen to be doing something to be approved of is greater than the desire to actually do it . . . . Recent years have seen the arrival of flash mobs—distracted spectacles of apolitical ‘communities’ incredibly quickly co-opted by ad campaigns and “spontaneous” fake demands to bring back old products (chocolate bars, crisps) that people dimly remembered from their childhoods. These ironic displays nevertheless hint at a subterranean desire for both spontaneity and a more genuine sense of belonging: popularity without the need for populism. In the twentieth century, the right-wing, or more broadly reactionary, tendencies of political and social life have historically been much better at attempting to inculcate a “true” populism (mass rallies, mass use of propaganda cinema, etcetera), although the Soviets were the first to see the potential of reproducible poster art and an international cinema (albeit in one country) . . . . Trapped between a commodity culture obsessed with creating fake-popular campaigns, and Facebook-organizing racist thugs, the future of populism doesn’t look great: against this depressing populism, our own recourse is to reclaim the notion of popularity when and where it emerges.

But how can we separate true popularity from false? Is anything allowed to be genuinely popular without immediate recapture by media and consumer culture? A hint here would be to observe when and where the numbers game is fixed, when precisely people don’t want you knowing how many people are involved. Every protester and activist knows that when the police give out their figures for protests it’s usually a quarter to a half of the real numbers; the same goes for media coverage—the crowd was barely there! Even in the arena of the basely numerical (that is, all contemporary human life), we can see the cracks in the edifice of populism against popularity. These moments of genuine popularity may be overwhelmingly motivated by anger and injustice, but perhaps this is as good a starting point as any, and perhaps the only one we have available to us in our current predicament.

Nina Power is a senior lecturer in philosophy at Roehampton University and the author of One-Dimensional Woman (2009).

Part of this contribution was previously published on January 17, 2011 on Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain (www.onlineopen.org/populism-without-popularity)

Oleksiy Radynski

Does a co-optation of oppositional or left political ideas, phrases and images by capital weaken or even empty these ideas of their political significance, radicality, and potential? What are the psychological and social effects of this persistent stream of neoliberal broken promises?

Why focus on the co-optation of the left by market forces? Why not reverse the question? At least once in modern history a leftist political project was able to appropriate and utilize the cultural language and imagery of capital to an extent which is comparable to the current submission of the left to capitalist needs. I’m talking about the October Revolution and the early years of the Soviet regime.

The enigma of market forces absorbing and digesting radical ideas might look less puzzling if we have a closer look at the Bolshevik government’s success at establishing its hegemony in arts and culture. Not unlike the ways in which the capitalist cultural industry is co-opting the subversive discourses of the left to its own ends, the communist government of the early USSR embraced and utilized numerous cultural practices borrowed from the capitalist past (and, in many instances, from the capitalist present). From slapstick to skyscrapers, from Freudism to Taylorism, the list of Soviet appropriations and co-optations is endless—and, unlike the market-driven New Economic Policy of the mid 1920ies, most of these trends in some form survived the advent of hardcore Stalinism. What happened when these ideas and practices were finally absorbed by Soviet culture? Were they the Trojan horses that ultimately neutralized the revolution? We’ll never know, unless the left’s radicalism and utopianism are absorbed by the market to an extent that they start decomposing it from within—just like rock music and auteur cinema allegedly helped to decompose the Soviet state. But this, so far, is nowhere to be seen.

Do you consider this co-optation to be a new phenomenon? If you don’t think it is a novel development, what is an applicable timeline for comprehending this kind of appropriation historically? Whether repurposed or new, are co-optations in recent history distinct in some way and/or do they correspond to a particular (cultural, political, historical) event or development?

An applicable timeline for this phenomenon could be deduced from the way the Western civilization structures its calendar. Anno Domini is a historical period defined by a never-ending endeavor to neutralize, domesticate, co-opt, if you will, the teachings of a fierce communist campaigner called Jesus Christ. Are co-optations in recent history distinct? The Sanders supporters have a choice of voting for Clinton or Trump, whereas some early Christians could choose between Orthodoxy and Catholicism.

Can you think of examples of effective/critical appropriations on the part of the left in recent history?

A near-total appropriation by the left of Western academia and the discourses that dominate contemporary art is certainly impressive. It could end up, though, that the price of this success is a near-total appropriation by the right of mainstream public debates in the West. Slavoj Žižek might be a no less spectacular speaker than Donald Trump, but what makes a real difference is that Žižek already lost his presidential election (in Slovenia). Yannis Varoufakis is launching his new political project in a leftist theatre in Berlin, which is soon to be taken over by a former Tate Modern executive (prompting mass protest resignations on the part of the theater’s creative staff). Every new Berlin Biennial proves that all those who hated its 7th edition were terribly wrong. The zeitgeist of 2012 was reflected in the sanctioned occupation of the ground floor of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art by activists, while the zeitgeist of 2016 is in the censorship of Trevor Paglen’s and Jacob Applebaum’s TOR piece at Pariser Platz, as Deutsche Telekom got paranoid about a sudden increase of encrypted traffic in the proximity of the US Embassy, and the piece was temporarily shut down.

Oleksiy Radynski is a filmmaker and writer based in Kiev. He is a member of Visual Culture Research Center, an initiative for art, knowledge, and politics founded in Kiev.

Martha Rosler

Do you consider this co-optation to be a new phenomenon? If you don’t think it is a novel development, what do you think is an applicable timeline for comprehending this kind of appropriation historically? Whether repurposed or new, are co-optations in recent history distinct in some way and/or do they correspond to a particular (cultural, political, historical) event or development?

Cultural appropriations are not a one-way street; ideas, images—including, of course, memes—flow back and forth, over and under, borrowed, wrenched apart, regrouped, repurposed, refitted. Co-optation is a harsher word than appropriation, presupposing the adoption of utterances of the (relatively) powerless for the purpose of reinforcing existing arrangements. To co-opt something is, as the American left has used the term, to rob it of its intentions for action in the public sphere or public arena and situate it in the lap of power. Political ideas are redefined and slogans trampled, positioned, and defined negatively or positively depending on what works. Tactical campaigns can be borrowed and placed in a different context, and examples are easy to find in the recent history of the United States (for example, the unapologetic cannibalization of relatively recent campaign slogans by Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, such as swiping “Make America Great Again” from Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign or adopting the loaded Nixonian phrase “law and order”). But this is neither a recent political development nor confined to the U.S. Religious syncretism (for example, colonial Latin American Catholicism) is in effect a practice of co-optation of existing organizing belief systems through amalgamation.

The important thing, in each of these cases, is to recognize as clearly as is possible, who is saying what and to what end.

After the rise of the modern women’s movement in the late 1960s, the Catholic Church set up copy-cat women’s organizations; in this they were not alone, as the political right wing did as well, in both cases presenting themselves as representing the true face and interests of the mass of ordinary women. (New York State’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, revived this tactic during his 2014 reelection campaign, when—facing allegations of corruption—he established the Women’s Equality Party to draw votes from his female opponent, the law professor and anti-corruption fighter Zephyr Teachout.) Along with these structures go a range of set phrases, from “America First” to slightly less filled out political phrases like “Law and Order,” to single words like “justice”—terms captured from national mythologies and ideologies that are inserted into counter-narratives: “No Justice, No Peace” (presently, “No Justice, No Peace! No Racist Police!”) or “Justice, Just Us.”

The advertising industry has long trafficked in impersonation and cooptation. Even before the birth of the advertising industry, however, product promotion has as a strategic move commonly relied on exaggerated or frankly false claims: the virtues of snake oil are notoriously backed by testimonials from shills. In medieval Europe (and subsequently elsewhere), town criers, or bellmen, officers of the court who read aloud public notices and news, also might be paid by merchants to tout their wares, acting like forerunners of radio and television announcers.

In modern sales campaigns for household items and cosmetics, the voice of authenticity migrated from any of a panoply of admired, presumably trustworthy actresses, especially young “starlets,” into the mouth of the woman in the kitchen or the man in the street—the ordinary housewife or ordinary joe, typically played by models or, eventually, by people who seemed too far short of the physical ideal and too unpolished to be anything but genuine, though it goes without saying that mostly these were paid actors. (Presently, the ordinary zhlub, usually a youngish, often pudgy man, is played for laughs, and although people recognize the slacker or couch-potato figure, the target viewer understands this as a comedic caricature of himself and bizarrely likes what he sees.)

Early 1980s’ television ads, to suggest authenticity, borrowed the shaky look of long-take, hand-held camera footage, mimicking the “direct cinema’” of the 1960s (or the shooting style of Candid Camera, a TV show in which ordinary people, taken in by some kind of ultimately harmless prank, are both humbled and elevated by having been acknowledged in their tiny window of fame–reality shows without the intensity of shaming.) By the 1980s as well, TV commercials were made by people who’d also been exposed in art classes to video art, originally the ultimate alternative form, and some video artists went to work for the industry full time or as day jobs.

So, it’s not new; it’s advertising. Certainly by the 1960s, with the development of the gigantic postwar market of baby-boomer young people in an era of rising incomes, the data wranglers (now called quants) began segmenting the market into taste classes. This is when the term “lifestyle” was given a new life as a focus of research and public discussion, especially by the Stanford Research Institute, the “think tank” established by Stanford University in Menlo Park, California. The adoption of “lifestyle” was meant to convey that one lives one’s life according to an array of conjoined consumer choices. In other words, lifestyle is a marketing term, around which a set of powerful diagnostics were developed in the late 1970s, to create a psychographic (a marketing neologism meant to contrast with demographics) methodology to measure and help shape U.S. values and buyer behaviors.

We can look to books like Paul Fussell’s Class, and others, in which populations are segregated not only by class but within class, into affinity groups and groups for whom tastes formed the locus of identification. Let’s note as well Richard Bolton’s analysis of the use of the term “revolution” by corporate America in the 1960s in order to capture the demographic bulge constituting the youth market.

The tracking of consumer behavior (i.e., “choices”) in real time is easily symbolized, as Brian Holmes has done, by reference to the Nielsen diaries of television watching solicited during the 1960s and later in which people self-report their television viewing, a process rife with pitfalls relating to sample selection, execution, and interpretation. According to an old industry saw, “Half of all advertising works; if only we could figure out which half.” Now, tracking of consumer choices, particularly relating to the digital world, is on its way to a microscopically fine-grained knowledge of actual consumer preferences, rendering irrelevant the attempts at divining the popularity of television shows or more importantly the effects of advertising, since that is the heart of the issue.

The twentieth century saw a revolution in the mode of representation, with new media technologies upending the understandings and expectations of how information is gathered, synthesized, disseminated, and received. Although it is in the realm of consumption that these changes are most obvious, it is their impact on political habits and institutions where the greatest effects are in play. Ideological message control by nation states and by such agencies as the CIA (running so-called psy-op or disinformation campaigns of destabilization), as well as supportive media outlets, is constant. If in war the first casualty is truth, in present-day political messaging this war, for hearts and minds, for financial support and votes, is waged against the population, in an ongoing pacification effort. As current political campaigns (Donald Trump’s, certainly) have demonstrated, with the right degree of celebrity splash and braggadocio, one can dispense with paid campaign advertising, for the media will provide free coverage. This persona polishing, having been staged primarily outside the political sphere, makes its bearer appear more authentic to followers, just like in fake-real ads. (“Outsider” status is a perennial populist phenomenon, and the contemporary European versions have won their following through years of messaging and organizing, channeling working class and nationalist discontent.)

We can say that artists, early in the postwar period in the U.S., began to understand the threat to their cultural standing and influence posed by the rise of the mass media. Whether we agree or disagree with Adorno-Horkheimer or with Guy Debord, or even with Allan Kaprow, in their views of the increasingly totalizing reach of the mass media and particularly television, in the contest between high art and celebrity culture, celebrity culture is winning: the structures of celebrity underpin or subsume the ways in which art and artists are discussed. If this war is not always in the forefront of our analyses, it is because it has become naturalized. The avant-garde revolt in the mid 1960s against institutional gatekeepers, commercial dealers, and other commodification engines of art-world circulation led to the development of mass-producible forms (related to the “dematerialization of the art object” thesis) but also to a move away from a search for meaning in primary nature, from the true, the beautiful, and the sublime, and from expressionism, toward an engagement with second nature, namely, the products of human-made but specifically commercial, corporate culture. The ever-canny Andy Warhol may have begun with supermarket items, but he understood the power of news, both articles and photos, especially of the famous and the abject. But unlike most other artists, he articulated the desire to be plastic and, in effect, flat—depthlessly in thrall to the world of publicity, with all its devious unreliability and patent lack of concern for truth or meaning.

The market’s appropriation of left symbolic language reverses artistic appropriation practices in which commercial communications are uncoupled from their intended logic and rearticulated to include an alternative political message. Is it possible to imagine signifiers that cannot be appropriated or “detourned” to ideologically opposing ends?

Appropriation, a late 1970s/early 1980s Pop (or post-Pop) strategy, can be read as a further step toward combating the ever-swelling tide of popular culture. This conscious echo of the aims of earlier, prewar European avant-gardes to tear down the barriers between art and life was soon compromised by a desire to grab some of the mythical aura of mass-culture celebrity on the way into the wider world.

You employ this interesting phrasing: “The market’s appropriation of left symbolic language reverses artistic appropriation practices in which commercial communications are uncoupled from their intended logic and rearticulated to include an alternative political message.” I’m not certain I agree. There is a difference between uncoupling, or severing, which in practice often simply amounts to selling low-end goods with a high-end price mechanism—buying something at a store and selling it at a gallery—and subversion or détournement. This rationale avoided exposure as blatant self-deception since the subversives rose to the top of a newly (re)founded art market—and the general mood seems to have moved toward one of semi-capitulation or, perhaps more charitably, to reimaging the true battlefield for art as residing on other fields: Any battles are pitched elsewhere, not perhaps primarily located at the level of the image but rather at that of thematics. Or perhaps we should say that we’ve given up on appropriating advertising in favor of political speech and have moved to other forms of enunciation, other forms of resistance.

We might then better ask if “social practice” is still in any way functional to its own aims of serving the “community” or has it lapsed back into being a low-paid, embedded service of containment on behalf of those social and political elites that are pleased to fund and promote it, as a secular version of charity and personal redemption. The question remains whether this is more or less of a co-optation than the assimilation into the discursive strategies of the state.

Since we operate under the rule of irony, I would say that no, it’s not really possible, at least at this conjuncture, to imagine signifiers that cannot be “flipped”—short of direct invocations of violence (“Off the Pig,” anyone?), which are either going to turn away your fan base from the outset or call down the wrath of the ad hoc committees of denunciation. As I’ve previously written, modes of resistance in cultural fields are not formulaic or fixed but need to be constantly reinvented. The market tends to sweep all marginal utterances in toward the center and, in the accelerating search for the novum, has become increasingly tolerant of critique—perhaps perversely so—as long as any negativity is largely confined to the symbolic realm. But this is in no way to be read as a reason to quit engaging. More broadly, as we know, artists have in many periods and many places refused to confine their alignment with crucial political struggles simply to the symbolic register.

Martha Rosler is an artist.

Haim Steinbach

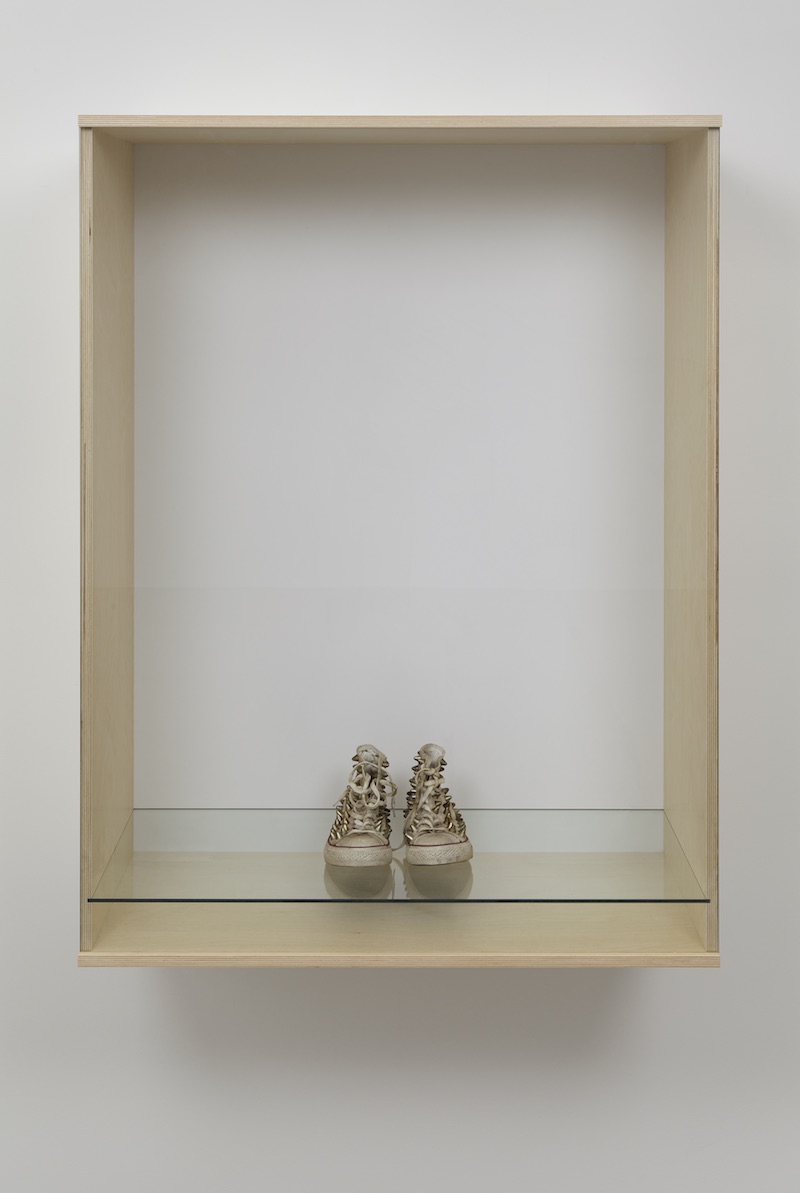

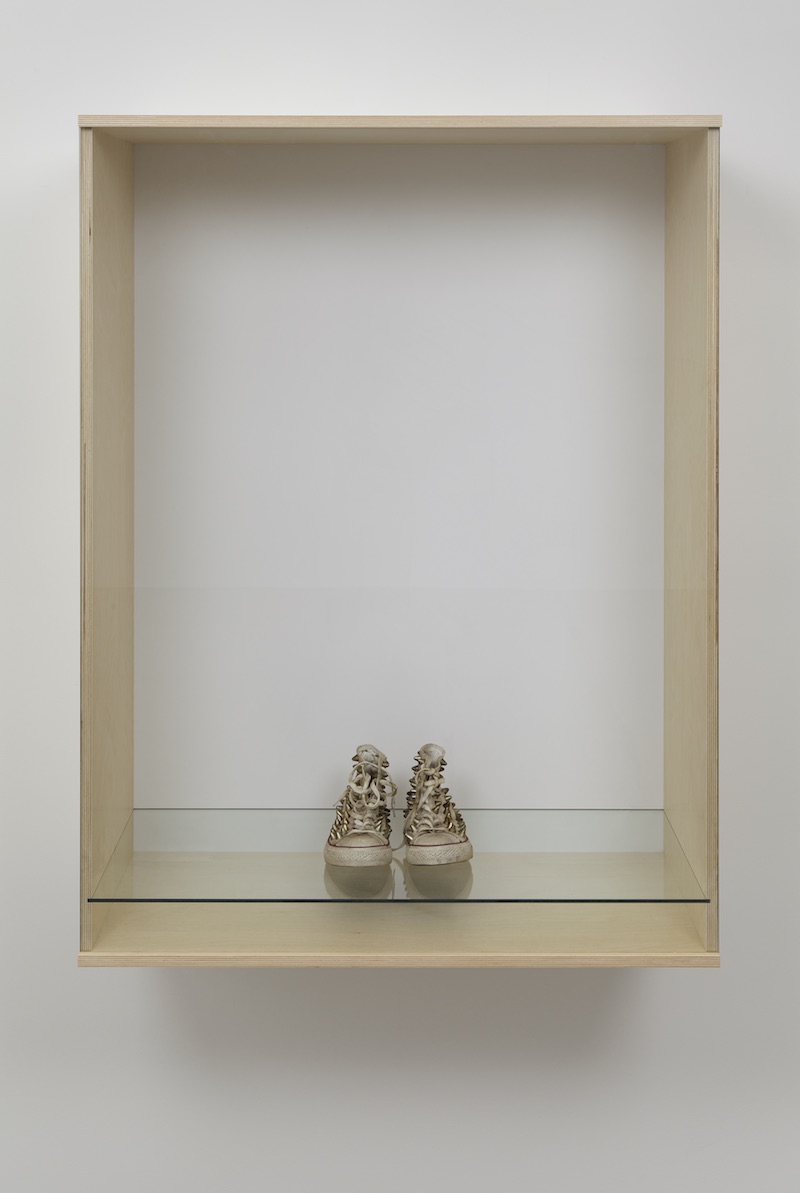

How is it that oppositional and leftist ideas are co-opted by the market? Do we mean co-opted by the Super PACs? Are the academics in the arts and the curators in museums as well as the artists co-opted? Or is it simply a matter of social classes and human nature. Is it possible that curators, academics, and artists may be envious of artists whose artworks have reached astronomical figures in recent years? Have some chosen to align themselves with some of these successful artists? And anyway who is upholding leftist ideas? Would it be Bernie’s young followers? Or does oppositional mean something else than being left or right, that may bring a psychological critical perspective on reality? Take, for instance, Maurizio Cattelan’s Him, 2001; is it an oppositional art work? What does it say about the market at this moment in history? And what does this say about society, globalism, and taking an oppositional stance? This work recently sold for 80 million dollars!

Haim Steinbach is an artist.

Etienne Turpin

Does a cooptation of oppositional or left political ideas, phrases, and images by capital weaken or even empty these ideas of their political significance, radicality, and potential? What are the psychological and social effects of this persistent stream of neoliberal broken promises?

These seem like different questions to me, or they imply different lines of thought; the first question is asking how the appropriation of a “left” imaginary by capitalism weakens that imaginary, but the second question asks about the effects of neoliberalism. These are different problems, and if we aren’t careful, we risk constructing a vague, general horizon against which our practices blur and become indistinguishable. Allow me to try to untangle a few threads of my own thinking as a reply. First, we would need to determine how an idea, image, or discourse is “leftist.” What is essentially “leftist” that is being appropriated? We could follow Walter Benjamin’s analysis here, as it is very clear and precise. Benjamin calls all the consumerist, technical “solutions” which capitalism offers to social problems “wish-images.” When political struggles and social action are rendered as wish-images, Benjamin is doubtful of them retaining any revolutionary potential. I would agree on that point, emphatically.

But, regarding the second question, it is clear that the failure of wish-images to deliver any meaningful social change rarely—at least rarely in our North Atlantic modes of consumption—leads to any serious questioning of these images. Neoliberalism, as a mode of governmental precarization (analyzed so clearly by Isabell Lorey), doesn’t exactly break promises, and we should be wary of personifying these processes. Instead, on the one hand we have a logic of accumulation under capitalism that must “promise,” through product arrays, types of exoticized leisure, lifestyle branding, and pleasure optimization, etc., a utopian mode of existence; on the other hand, we see an increasing precarization of life as all forms of social welfare are stripped bare through cuts and privatization. The relation between these two processes is far more complex than we could analyze meaningfully here, but I would be very cautious about drawing general conclusions. The “branding” of consumption as a mode of social change is extremely problematic, but to address this problem would require much more than asserting the “essentially leftist” character of the imaginary being invoked through logics of consumption. Thinking the machinic dimension of appropriation requires a much greater attention to details of interaction.

Do you have an example of this phenomenon and its implications?

I work and live in Jakarta, Indonesia, where there is currently underway a process called “normalization,” which involves the eviction and displacement of tens of thousands of families from difficult-to-formalize areas; this involves businesses, residential areas, hawker carts, and other portable modes of commerce, and a variety of ecological systems including the waterways and the coastal areas. In addition to this massive urban reconfiguration, there is currently a massive 25 kilometer long sea wall under construction that will enclose Jakarta’s Bay in the Java Sea and produce a second city for the wealthy floating on the coast. Now, whether or not one believes this can be executed in reality, it is underway, and the important thing is that even those who will be displaced by the Great Garuda Sea Wall (comically, it is figured as nationalist, mythical bird that will protect the city) are often found cheering for this infrastructure. If we believed in ideology, we’d say: these people are fooled—they are cheering for a project that is against their own interest. But, I am trying to articulate instead a theory of cruel enthusiasm, which departs from the neurotic, object-scale of investment described so well by Laurent Berlant, to examine the collective investment in modes of violent expulsion. How is cruel enthusiasm produced? What is its specific formation in Jakarta? How did we come to a point where an unqualified “normativity” could stand in as the objective of such a violent urban process, one which is supported by such a large number of residents?

Do you consider this co-optation to be a new phenomenon? If you don’t think it is a novel development, what do you think is an applicable timeline for comprehending this kind of appropriation historically? Whether repurposed or new, are co-optations in recent history distinct in some way and/or do they correspond to a particular (cultural, political, historical) event or development?

I think the ways in which the social body invests in imaginaries must be studied more closely, with more attention to historical details. I live in Asia, where we can see any number of overlapping, conflicting, even “contradictory” logics folded into one another in novel ways. In North America, we were discussing co-optation in the late 1990s as activists concerned with economic injustice. Of course, almost 20 years later there are many serious differences. Things we used to argue about capitalism back then are now commonplace claims—not even the least bit radical today. But that is less a matter of co-optation than the result of witnessing capitalism unfold, globally, over the last 15 years or so. No one can pretend any longer this is anything but a system of mass destruction! But, the blinding argument that “there is no alternative” seems to stick, even today, even if the system to which it refers has revealed itself as a horrific nightmare. From this perspective, co-optation seems to be a fairly marginal struggle, an epiphenomenon of a much more complicated, violent, disbursed, but coherent process of expulsion and dispossession.

The market’s appropriation of oppositional or counter-cultural ideas reverses artistic appropriation practices in which commercial communications are uncoupled from their intended logic and rearticulated to different political ends. Has the market’s increasing ease in appropriating artistic critique and left political imaginaries caused you to question or reconsider strategies of resistance?

I think, for the most part, radicals, especially many academic radicals, don’t really know what they mean by resistance today. We are completely fucked. The hostility to any mode of existence that attempts to oppose, escape, or undermine the logic of accumulation is profound and brutal. And, for certain, such violence can’t be confronted by peer-review publications or biennials!

Is it possible to imagine signifiers that cannot be appropriated or “detourned” to ideologically opposing ends?

I believe such a proposition fails to grasp the process of semiotization which characterizes our present situation. Instead, consider the following remark by Michel Foucault: “I do not think that there is anything that is functionally—by it very nature—absolutely liberating. Liberty is a practice. So there may, in fact, always be, a number of projects whose aim is to modify some constraints, to loosen, to even to break them, but none of these projects can, simply by its nature, assure that people will have liberty automatically: that it will be established by the project itself. The liberty of men [sic] is never assured by the institutions and laws that are intended to guarantee them. This is why almost all of these laws and institutions are quite capable of being turned around. Not because they are ambiguous, but simply because ‘liberty’ is what must be exercised.”[i] So, while the co-optation via semiotization is not the same as the socio-spatial logic described by Foucault, the point is nevertheless clear: there is no such thing as a space, or a sign, that is emancipatory in itself, because the extension of space and the enunciation of a sign cannot be distinguished from their context or meaning. Said differently, the frontline is everywhere.

What is the contemporary status of spectacle in this regard (do you consider this form of communication an available, necessary, or rather ideologically predetermined tactic for cultural producers on the left)?

If we move on to a Debordian analysis, I suppose we’d have to accept that in the logic of the diffuse spectacle (as Debord himself suggested in 1988), there is necessity despite its ubiquity. It is a historical condition, not a necessary one. It is the water we are in, and so, as a philosopher, designer, and organizer, I believe we have to operate in the field of our struggle, which is rarely one we get to choose.

But, we should emphasize that most academics produce this diffuse spectacle exquisitely. Legions of cultural theorists can perform this armchair criticism from inside their universities well—but they perform critique only as a residual function, while their primary activity is the sale of debt to their students. They promote a lifestyle brand of the thoughtful, critical academic; they inhabit the role of an advertisement, which is the sale of a life of debt to their students, a transaction which they legitimize by professing their criticality of the system they produce. What could be a more miserable ecology than that of petty debt-salespeople acting out their micro-fascist jealousies through demands for more obscure criticality from their increasingly indebted students?

There is nothing that says writing articles, chasing tenure, selling debt to students, or writing paywalled articles could or should meaningfully address the confounding power of the spectacle—image-capital—and the violence required and advanced by accumulation. Instead of getting our knees dirty with all this sycophantic academic posturing, we might need to get our hands dirty in making a world where both thought and struggle are still possible.

Can you think of examples of effective/critical appropriations on the part of the left in recent history?

If we think of effective counter-appropriations, we need to turn our attention to infrastructure. How to fight for, maintain, and extend infrastructure for emancipatory political and environmental struggles. These are real struggles, and they will continue to occur around the globe; but, it seems prudent to allow the ones that are working the best to stay underground, away from the cultural spotlight of biennials which attempt to syphon them into the logic of accumulation by making them commodified cultural products. ;-)

Etienne Turpin is a philosopher studying, designing, curating, and writing about complex urban systems, political economies of data and infrastructure, art and visual culture, and Southeast Asian colonial-scientific history.

[i] In Foucault Live, Collected Interviews, 1961–1984, p. 339

Dmitry Vilensky

Does a co-optation of oppositional or left political ideas, phrases, and images by capital weaken or even empty these ideas of their political significance, radicality, and potential? What are the psychological and social effects of this persistent stream of neoliberal broken promises?

Speaking from a conservative part of the globe, Chto Delat encounters very few of the challenges posed by this kind of instrumentalization, but of course we are familiar with it. It also frequently happens that our own work is placed in some dubious context. First of all, I think this situation marks the general weakness of the leftist agenda, thus enabling the capacity for it to be used by capital. The only possible answer would be to gain strength: to build a serious counter-cultural hegemony where references to an emancipatory project would entail a real threat to the current status quo. But we are far from that at present.

Do you consider this co-optation to be a new phenomenon?

I think the rhetoric of emancipation has always been more sexy and full of energy than the conservative agenda. That is why it is widely implemented by turbo-capital, which also has stakes in the project of world transformation. There is nothing particularly new about this phenomena—what is novel is the scale and its media distribution.

The market’s appropriation of oppositional or counter-cultural ideas reverses artistic appropriation practices in which commercial communications are uncoupled from their intended logic and rearticulated to different political ends. Has the market’s increasing ease in appropriating artistic critique and left political imaginaries caused you to question or reconsider strategies of resistance?

To some extent, yes. I think we started to escape the language that opts for “easy readings” and tried to be more opaque and more arrogant in our communication with the mainstream art world.

Is it possible to imagine signifiers that cannot be appropriated or “detourned” to ideologically opposing ends?

I think that signifiers that cannot be appropriated always exist. However, the market is not a totality; it only appropriates things which can create a quick profit. If you slow down a bit, and think and exist in another temporality and geography, then I think you could become rather invisible. But how do you then create influence? I believe that there are certain “grey zones,” which have their own power but remain rather invisible in market terms. We should celebrate “the waste” of artistic creation and find our own way to claim its value.

What is the contemporary status of spectacle in this regard (do you consider its form of communication an available, necessary or, rather, an ideologically predetermined tactic for cultural producers on the left)?

We have an old slogan on our banners: “Educate—entertain—inspire.” The trick is that the three come as a unit, not separately.

Can you think of examples of effective/critical appropriations on the part of the left in recent history?

It depends what you call appropriation. I consider it very important that the majority of leftist politics have also been manifest in artistic creation and that they have become part of the dominant curriculum in this form. Of course anyone could say that the messages of these works are castrated and neutralized when they are incorporated into the museum or academia, but we do not have other ways for expansive knowledge sharing and, even from within these institutions, these traditions can be subject to reclamation by new generations. New generations need to have access to them and their living memory. To a certain extent, appropriations secure this possibility, albeit in a paradoxical way.

Dmitry Vilensky is an artist and a member of the collective Chto Delat.

Soyoung Yoon

“Be realistic, demand the impossible!” What is the status today of the 1968 demand for the impossible, for the radicality of change, for the necessity of this radicality, if change is not to be a mere amendment to the status quo, if change is to be real? What about the category of the impossible?

A case study: the photograph is of a small Nenets child, in a snowbank, reaching out to pat the forehead of a baby woolly mammoth fossil. The latter, named Lyuba (a diminutive form the Russian word for “love”), is considered one of the most well-preserved and complete mammoth fossils discovered to date; the mammoth died about 42,000 years ago, at approximately one month old, and its fossil is currently on display at the Shemanovsky Museum. The ideological function of the photograph is precise: the child’s gesture is presented as one of curiosity, fear, and sympathy, as it reaches out to another, similarly-sized figure of childhood that seems to blur the living and the dead, the possible and the impossible, bridging not only a difference of species but a duration of time almost unimaginable. And this encounter with the presentness of the past is represented as a return to an eternal childhood—that of any child, every child—an ahistorical, nostalgic evocation of universality, further underscored by the Nenets child’s garb, the traditional clothing of a pre-modern culture that is supposed to have withstood not only the Siberian arctic, but also the 20th and early 21st century. The past is not only graspable but it is also surprisingly well-disposed and accessible, profoundly “friendly”: a domestication of the past, where it (re)appears not so much as “Adam” as a pet.

This particular photograph has been repeatedly appropriated by the would-be latter day prophet Steward Brand, the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog (1968–72) and the co-founder of The Long Now Foundation (1996–), to illustrate the significance of the project “Revive & Restore,” which seeks to advance genomic technology to resurrect endangered and extinct species for purposes of conservation. The project exemplifies the brazen defiance of the counter-cultural ethos Whole Earth Catalog, its exaltation of the power of individual enterprise, which continues to serve as the ideology of Silicon Valley and its technophilic, corporatized libertarianism: “We are as gods, and we might as well get good at it.” In the case for the revival of the woolly mammoth, the claim is to restore the grasslands by repopulating the tundra and boreal forests with grazers such as the mammoths; the newly restored grass would reverse the accelerated melting of the Arctic permafrost, which would release excessive quantities of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere and further exacerbate global warming. The problem of global warming then is approached via a circuitous route of almost absurd proportions, as if it were easier to imagine the ecosystem via the spectacle of a gigantic Rube Goldberg machine. The linear, mechanical causality of one-after-another appears as a natural law. And that “law” would contain and resolve social-economic contradictions with severe consequences for an increasingly acute global polarization of inequality (of which climate change is a part).

According to this fiction of “nature,” death too could be resolved, no longer irrevocable, incorporated as part and parcel of that one-thing-after-the-other: There is no end that cannot be undone, no finitude, no limit, or as Marx would critique, “thus there has been history, but there is no longer any.” As the photograph illustrates, the dead that is resurrected (or exorcized) is imagined as dormant and benign, one that bears invaluable genetic information but no memory of the history that caused its extinction nor its current revival, a past that returns not with the force of the repressed, the rupture of radical difference, but with a friendly pat on the forehead.

Walter Benjamin spoke of how the child grasps for the moon as it would for a ball, “so every revolution sets its sights as much on currently utopian goals as on goals within reach.” For Brand, however, the scenario is reversed: The moon is the ball, brought down to earth, part of a project for the “long now,” a perpetual present in which there is no rupture of the past or the future. And the demand is not for the impossible but for the impossible redefined as that which is probable, a problem of capacity, skill, and ingenuity. We are as gods, so we might as well… The iconic slogan of May 1968 would have to be inverted into a conservatism that but proclaims change in attitude, posture, and style: “Be impossible, demand the realistic.”

Soyoung Yoon is Program Director and Assistant Professor of Visual Studies, Department of the Arts, at Eugene Lang College, the New School and faculty member at the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program.

Benjamin Young

In 1983 Douglas Crimp argued that the apparently critical tactic of appropriating images from mass culture could be, and was, appropriated by the forces it was directed against: “The strategy of appropriation no longer attests to a particular stance toward the conditions of contemporary culture… Appropriation, pastiche, quotation—these methods extend to virtually every aspect of our culture, from the most cynically calculated products of the fashion and entertainment industries to the most committed critical activities of artists.”[1] While the ubiquity of this new mode of cultural production heralded a major cultural shift from modernism into postmodernism (a shift that Crimp saw as partly inaugurated in the work of Robert Rauschenberg, but certainly also including Pop), it tells us little about the political valence of specific practices. Seeking to address different kinds of appropriation, Crimp detected changes in the work of Pictures-generation artists—specifically Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince—whose “practices begin, even if very subtly, to accommodate themselves to the desires of the institutional discourse [of art] . . . they allow themselves simply to enter that discourse (rather than to intervene within it) on a par with the very objects they had once appeared ready to displace.”[2] In other words, the process of “appropriating appropriation,” as Crimp called it, is a long and ongoing one that involves not only the co-optation of critical practices by the market but their own accommodation to its terms and the terms of other forms of power. More broadly, that capitalism should attempt to appropriate and disarm the radical political imaginaries of the left is no surprise. To rewrite William S. Burroughs’s epigraph to postmodernism (itself already a quotation): in the struggle of hegemony, nothing is safe, and everything is permitted.

Are things any different today? I admit I am not very interested in contemporary art that endlessly adopts the form of, and thereby reflects on its own co-optation by, advertising, commodification, or capitalism tout court. Even less compelling are works that produce a mise en abyme of revolutionary slogans assumed to be always already co-opted by the commodity form in which they are presented and which smacks of radical chic, cynicism, and bad faith. I want to propose that this irony and formal reflexivity can be grasped through a rather different post-revolutionary moment, neither post-1968 nor post-1989: the Jena romanticism of the early 1800s. In a half-serious catalogue of different kinds of irony, Friedrich Schlegel wrote of the “irony of irony,” especially the reflexive kind that “turns into a mannerism and becomes, as it were, ironical about the author.”[3] Such self-reflexive irony may appear at first to throw into doubt the meaning, sincerity, or identity of the author or his statements. Yet through such irony, G.W.F. Hegel protested, “the ego can remain lord and master of everything”: an abstract, purely formal ego seems to be the source of all doubt and knowledge, so that, on one hand, through ironic distanciation, “every content is negated in it” and, on the other, any content that it embraces seems to be posited and recognized only by that ego, making the real only a semblance of it. [4] According to Hegel, Schlegel invented this “divine irony of genius” that is the “concentration of the ego into itself, for which all bonds are snapped and which can live only in the bliss of self-enjoyment,” in its own reflexivity.[5] Such a genius may produce artworks but primarily goes on “living as an artist and forming one’s life artistically.” By grasping his own life as a work of art, “this virtuosity of an ironical artistic life apprehends itself as a divine creative genius for which anything and everything is only an unsubstantial creature, to which the creator [i.e., the lifestyle artist], knowing himself to be disengaged and free from everything, is not bound.”[6] This irony takes another turn unforeseen by Hegel when postmodernism does away with originality as the criterion for genius and the ego instead paradoxically secures its “absolute freedom and unity” in and through appropriation—or what might be better called disappropriation—not by making alienated commodities or the debased detritus of capitalism one’s own, but rapidly recirculating (images of) them in order to show that one is not (fully) bound by or attached to them. (DIS’s online shop is called “disown.”) When this egotistical irony vacillates between adopting the language of capital or the commodity or advertising or corporate marketing and then formally, reflexively, ironically nullifying that embrace, it often functions as a kind of left melancholia that comforts the ego unable to mourn the loss of a political ideal. It becomes obsessed with the reflection of its own conflicted, doubled, and guilty image glimpsed in the art fair or market’s hall of mirrors.

This attitude of ironic embrace seems to provide a kind of secret society for those who feel a disidentification with capitalism or wish to resist it, but who do not outwardly speak of such resistance, or speak of it only ironically. Yet such irony allows this anticapitalist cryptocommunity simultaneously to function as a kind of cryptocapitalist anticommunity, an imaginary elite lifestyle, even if one formed from below or from the margins of the luxury market. Such an ironic lifestyle secures for the individual an imagined, abstract freedom and unity that allows one to enjoy the workings of capitalism (either as a consumer; or as an artist who produces images or objects for the luxury market; or, in the case of artistic appropriation, or meme generation, or as a contributor to social media whose content and clicks are sold by corporations to advertisers, as a consumer-producer or producer-consumer), all the while holding oneself apart from those who unironically fall for the seductions of consumerism, the workings of capitalism, the digital economy’s terms of service, or are unselfconsciously exploited by that system. Although I have given Hegel’s objections a materialist slant, we can begin to understand his contempt for the romantic ironist, and it is perhaps not a coincidence that Jena romanticism occurred as a bourgeois aesthetic revolution in the aftermath of, and perhaps in lieu of, the radically democratic revolution that had taken place in neighboring France.

But unlike Hegel, I am not interested in proclaiming the decadence or end of art and its supersession by philosophy or criticism; nor in restoring “genuine earnestness” or “seriousness” or the essential reality of morality or truth; nor in jumpstarting the stalled historical dialectic in order to get absolute Spirit—or in the materialist version, proletarian revolution—moving. (Although I’m all for stoking the class struggle). For a few reasons: One cannot simply leave such historically determined contradictions behind. And there are other kinds of irony, especially a certain irony of the bondsman, a cutting rejection of the master’s terms even while repeating to the letter his commands, which may be an indispensable aesthetico-political device that should not be hastily abandoned, even if it is never safe from appropriation, misunderstanding, or incomprehensibility.

Rather, I am more interested in two other approaches to this problem. First, there are less spectacular practices that challenge the material conditions of art and life under capitalism—that call attention to the tain of the mirror, as it were. I am thinking of how often activist practices take up the call to supplement reflection with action or praxis, although not always without irony. And although they frequently involve artists and art workers, they often don’t fall under the banner of art, which helps to avoid accommodation with its institutional discourses, but at the cost of losing access to the resources those institutions provide. A few examples I’m familiar with from New York: Arts and Labor, a working group that grew out of Occupy Wall Street, sought to analyze working conditions in the culture industry and help art workers organize themselves, including using creative direct action to support art handlers locked out of Sotheby’s or to pressure the Frieze Art Fair to use union labor. Gulf Labor and G.U.L.F. have similarly used media appeals and direct action to call attention to the abusive conditions, debt bondage, and violations of human rights entailed in the construction of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. While artist-advocacy organizations such as W.A.G.E. have importantly sought to challenge inequitable working conditions for artists, A&L and Gulf Labor have gone beyond advocating for the self-interest of artists, developing uncommon forms of cross-cultural and cross-class solidarity—in the case of Gulf Labor, with an underclass of globally migrant labor. Just recently, Martha Rosler restaged her 1989 exhibition on the politics of housing, If You Lived Here, and artists and art workers have been focusing on the Brooklyn Museum as a node in the gentrification of its surrounding neighborhoods, seeking to collaborate—and not always successfully, given their status as the avant-garde of gentrification—with activists in local communities, which are largely black and brown, already engaged in fighting urban displacement. Calling attention to the material conditions that sustain the institutions of art, such practices rearticulate the institutional frames of visibility that exclude those sustaining conditions from public view, as outside the realm of art or culture. And doing politics, they seem to show, is extracurricular; any comfortable certainty that art will have political force outside of a broader social praxis is bound for ruin. As Gran Fury put it, in an entreaty to take up direct action to stop the AIDS crisis in the midst of the allegedly simulationist 1980s, “art is not enough.”

This is not an argument for moral purity or a way of pining for an Archimedean point outside of capitalism, from which one could finally launch a thoroughly revolutionary critique. Nor is it an argument against being reflective about one’s own role in the reproduction of capitalism. It is clear that neoliberalism reproduces itself not only by ideologically capturing individuals as consumers at the level of desire and by exploiting them as laborers, but also by forcing them to become mini-capitalists themselves. In the U.S., this means loading young people up with education debt to keep them working in the consumer-credit economy, forcing the old to invest their savings in the speculative and volatile stock market, removing the protections of the social safety net with the eventual goal of turning all workers into full-time temporary freelancers in the gig economy of the future, and condemning those who don’t make the cut as entrepreneurs to the usurious limbo of predatory lending, payday loans, foreclosure or eviction, and finally social exclusion. And here, dear reader, is the less grave, but no less structural, irony of this text: by having agreed to write this response without getting paid, I have perhaps compounded the devaluation of critical discourse on the net and extended the self-exploitation and pauperization of precarious cultural workers producing content for free in an entrepreneurial gig economy that I otherwise oppose. I comfort myself with the irony that Crimp’s essay cited above appeared in the catalogue for Image Scavengers, a museum exhibition that was itself appropriating appropriation in ways he warned against. Of course, artists need to make a living as well, and selling work on the market is one way to do so, but it clearly entails contradictions within and limits to the work that can be done. Rather than an egotistical irony reflecting back on itself in the mirrored halls of the gallery or the internet, it may be time to embrace a different kind of worldly irony, if a not altogether tragic one.

Second, I am interested in the work of artists who are not afraid of content. By that I mean practices that, however reflexive about the formal, framing conditions for the work, move beyond the habits of cosmopolitan elites ironically surfing the flows of digital hypercapitalism. Often documentary in approach—and too numerous to list here—such more worldly practices can open onto other contradictions that are not often represented or examined within advertising, marketing, consumerism, fashion, or business corporations. Such practices have little time for artistic gestures of grand refusal or abject complicity, for diamond-encrusted skulls or 18-karat gold toilets. Stretching from the 24-karat gold bathroom fixtures on Donald Trump’s private Boeing 757 back to ultra-opulent CEO decorators such as John Thain or Dennis Kozlowski, those on the perp walk of corporate rapaciousness have already superseded the imaginations of artists. The question then seems to be: Does whatever irony at play in exhibitions like the Berlin Biennale manage to point beyond itself?

[1] Douglas Crimp, “Appropriating Appropriation,” in On the Museum’s Ruins (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 126.

[2] Crimp, 135.

[3] Friedrich Schlegel, “On Incomprehensibility,” in Friedrich Schlegel’s Lucinde and the Fragments, trans. Peter Firchow (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971), 267.

[4] G.W.F. Hegel, Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, trans. T.M. Knox, vol. 1 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), 64–5.

[5] Hegel, 66.

[6] Hegel, 65.

Benjamin Young is a doctoral candidate in rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley, who teaches the history of art and photography at FIT, The New School, and NYU. He is managing editor of Grey Room and worked with Arts & Labor.